- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Surrealism in Belgium: Exhibition ‘Histoire de ne pas rire’ reveals artists’ ambition to transform the world

If René Magritte is the poster boy for Histoire de ne pas rire. Surrealism in Belgium, this new exhibition at Bozar ambitiously traces the origins and evolution of the powerful 20th century movement.

Belgium’s flagship celebration of the movement’s centenary is also the banner event for the cultural programme of the country’s current presidency of the EU council.

Beyond Magritte’s iconic images, the exhibition presents three generations of Belgian artists and writers who for 75 years passionately and collaboratively forged their own avant-garde vision. Their inspiration and influence was formative to pop-art and persists today.

Following the horrors of World War One, André Breton published 'The Surrealist Manifesto' in Paris in 1924, pleading for insurgent, imaginary, anti-rational and unconscious artistic expression. This marked the official birth of Surrealism, with Breton adopting poet Guillaume Apollinaire’s name for something that was beyond reality. In the same year, three Belgian writers launched bold pamphlets challenging the spontaneity of these psychoanalysis-based notions, alternatively promoting humour as a subversive weapon to transform the world.

The towering influence of their intellectual figurehead, Paul Nougé, occupies a central strand to the exhibition. Its title Histoire de ne pas rire is borrowed from the name of his 1956 book, while another statement outlined the serious intention of the group. “How then did we not realise that before being a doctrine, Surrealism is fundamentally an attitude of mind?”

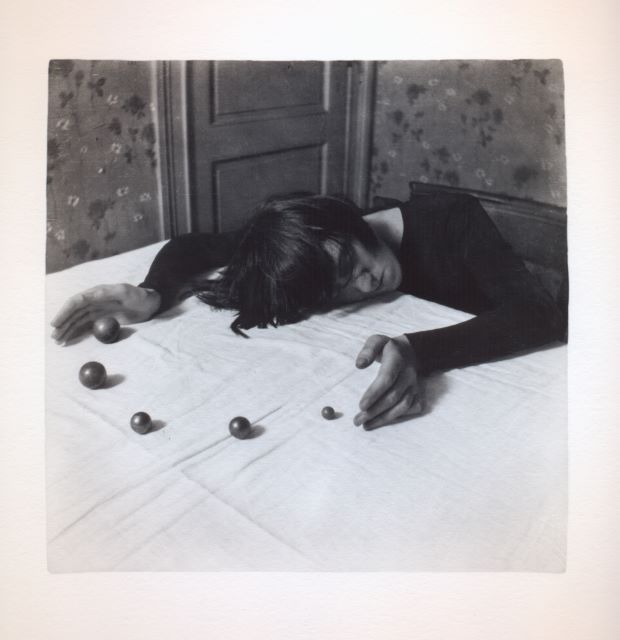

Nougé maintained a shadowy role in the movement; he believed artists should shy away from the limelight while pursuing political engagement. But he was a key advocate of Magritte, regularly providing enigmatic titles for his friend’s paintings. Apart from his writing, Nouge, a poet and biochemist, created just one work, a series of disturbing black-and-white photos, La Subversion des images. They each feature objects eerily removed or added (La Jongleuse, pictured).

A novel feature of the scenography for the 400 works on show is that the walls are reserved for texts while the 260 paintings are displayed on panels, alongside cabinets filled with the Surrealists’ many written works, witty and original cards and games. This creates a labyrinth if dense experience; the mirrored bottom and side sections injecting an illusion of space and distortion.

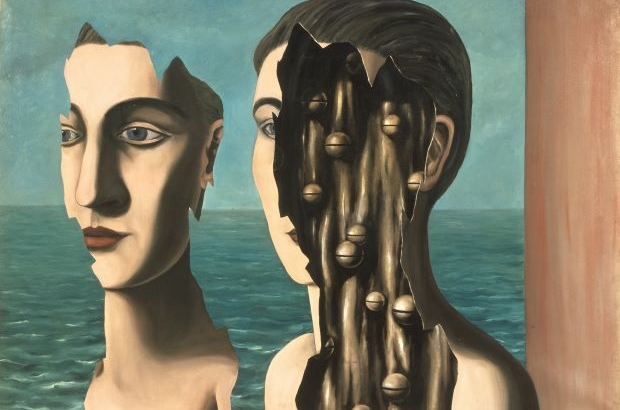

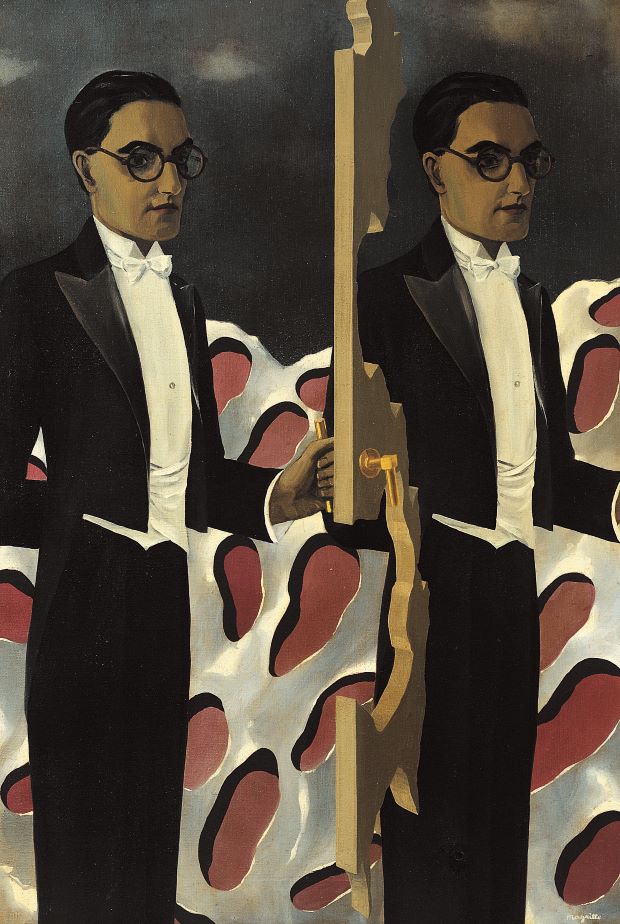

Paintings by Magritte naturally dominate. An early colourful abstract shows how the former commercial artist explored different styles in the 1920s, his work progressing as he encountered other artists. In a striking 1927 portrait of Nougé (pictured), he mysteriously doubles the figure of his friend. This practice was a cornerstone of his use of imagery, seen also in The Double Secret (main image).

The growing band of Belgians exploring Surrealism sought inspiration from international artists. Magritte and his wife Georgette moved to Paris in 1927, the capital of the art world. Among the artists encountered was Joan Miró, originally from Spain, who was exploring a distinct visual language in his collages.

Italian Giorgio de Chirico was another major influence with his bizarre early ‘metaphysical’ paintings, such as the 1912 The Delights of the Poet (pictured). Containing strange elements like illogical perspective and movement, it conveys an atmosphere of silent foreboding.

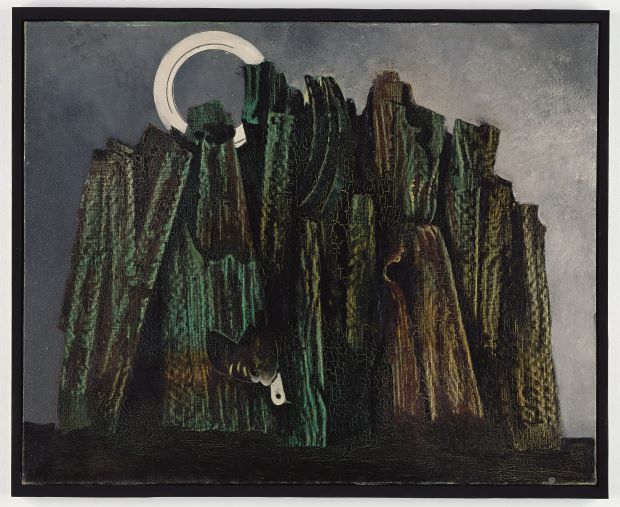

German Max Ernst was previously prominent in the Dada movement, the precursor to surrealism. Assembling random subjects, he developed his own technique for automatic art, the technique favoured by French surrealists. ‘Frottage’ was a form of brass rubbing on textured surfaces that the artist then stared at, drawing on his subconscious to make out hallucinatory creatures and stick figures (Dark Forest and Bird, pictured).

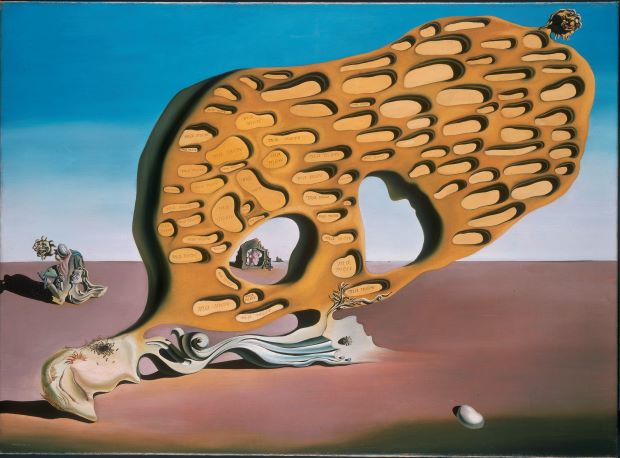

The Spanish eccentric artist Salvador Dali, was already producing fantastical multidisciplinary works, before propelling surrealism in another direction by painting dreamscapes. His reaction against reality is evident in The Enigma of Desire (pictured), a 1929 work of Dali embracing his father.

Despite their opposing characters, Dali and Magritte shared many common artistic themes, from incongruous objects to artificial light in a hyperrealist style to create a window into the subconscious. But the Belgian occupied an everyday world where mundane people, objects and houses are imbued with a strange and threatening existence. Nothing is what it seems in Magritte’s familiar but sinister universe.

This continual dialogue with artists from home and abroad proved to be a fertile artistic landscape. Magritte’s painting of a giraffe in a glass was a riposte to Dali in an ongoing visual dialogue (pictured). After the Spaniard’s painting of a giraffe on fire, the Belgian responded by incongruously placing the animal in a glass, transforming the insult into a mirage-like image diffusing loneliness.

An illustrious rollcall of other Belgian artists included Raoul Ubac, Leo Dohmen and Paul Delvaux. The latter absorbed playful elements of Surrealism; disparate subjects, forms and ideas, while maintaining his fascination for classical antiquity (The Pink Bows, pictured).

A local offshoot of the movement sprung up in the province of Hainaut in 1934, centred on the industrial town of La Louvière. A group of poets and writers called their group Rupture, reflecting the political climate of the time. After a first Surrealist exhibition in Brussels in 1934 (Minotaure), the group staged a second show of work in the mining town.

World War Two and German occupation disrupted all this creative fervour. Delvaux decided not to publicly show the series of dark works he produced during this period, Magritte sought solace in Impressionism in what is known as his ‘Renoir period’. After the war, he was invited to exhibit in a small Paris gallery. A little offended, he adopted a new outrageous style, known as the ‘période vache’. These colourful, instant expressions of emotion were a short-lived outburst.

Another generation of artists was emerging, including notably Marcel Mariën, who served as an apprentice to Magritte and assumed a pivotal role in the Belgian movement. Mariën was just one artist who transformed the female form into a canvas in order to shock and attack conservative institutions such as the church and bourgeoisie (pictured).

Nevertheless, women played an important role in the artist collective. If their influence has been overlooked, the exhibition showcases their alternative vision, in particular the work of Rachel Baes and Jane Graverol, both daughters of painters.

Baes was drawn towards Surrealism, frequenting artists within the movement while remaining on its periphery. Her dark often menacing works are loaded with meaning in a visual vocabulary distinct from her male colleagues. Childhood trauma is often depicted, such as in The Philosophy Lesson (pictured). Another painting details beautiful lacework, a valued Belgian handicraft that employed women in lowly-paid labour.

After working in a realist style, Graverol, explored Surrealism in paintings she described as ‘conscious dreams’. Cages and birds were frequent themes, as in Untitled (Liberated Woman), pictured. She was a major contributor to the literary review Les Lèvres nues founded by Marien and Nougé in 1954, also making a provocative and banned film L’Imitation du cinema that is screened at the exhibition. Graverol’s 1964 portrait of Brussels’ Surrealists The Drop of Water includes both herself and novelist and poet Irène Hamoir, indicative of their influence in the group.

In the early 1950s, a disagreement between Magritte and Nougé led to a division among the Belgian Surrealists. The painter distanced himself from the group’s political ambitions. Although the demise of Surrealism was officially announced in France in 1969 – Breton had died in 1966 – the movement persisted in Belgium. Prolific writer and collagist Tom Gutt revived a collective of artists and writers, consisting of old and new members, that continued well until the 2000s (Marcel Mariën’s The Tao, pictured).

From the beginning, Surrealism in Belgium followed a singular path. It has both contributed to the movement’s influence around the world and created a national identity and attitude centred on a subversive humour that continues to characterise the country.

Histoire de ne pas rire is curated by Belgium’s leading expert on the art movement, Xavier Canonne, who has edited the guide accompanying the exhibition (published by Mercator in French and Dutch).

A complementary exhibition, Imagine! 100 Years of International Surrealism is showing at the Fine Arts Museum in Brussels until 21 July, with a duo ticket providing access to both shows.

Histoire de ne pas rire. Surrealism in Belgium

Until 16 June

Bozar

Rue Ravestein 23

Brussels

Photos: (main image) René Magritte, The Double Secret ©succession Magritte – Sabam Belgium 2024; René Magritte, Portrait of Paul Nougé, ©succession Magritte – Sabam Belgium 2024; Paul Nougé, The Juggler, from the series Subversion of images © Rights reserved; ©Giorgio de Chirico, The Delights of the Poet ©Sabam Belgium 2024, photo ©Robert Bayer; Max Ernst, Dark Forest and Bird ©Jochen Littkemann; Salvador Dalí, The Enigma of Desire ©Sabam Belgium 2024, photo: bpk/Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen; Paul Delvaux, The Pink Bows ©Foundation Paul Delvaux, Sint-Idesbald - SABAM Belgium, 2024. Photo: Rik Klein Gotink; René Magritte, The Cut-Glass Bath ©Photothèque R. Magritte, Adagp Images, Paris, 2024; Rachel Baes, The Philosophy Lesson ©Sabam Belgium 2024; Jane Graverol, Untitled (Liberated Woman) © Sabam Belgium 2024; Marcel Mariën, The Tao ©Fondation Marcel Mariën