- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

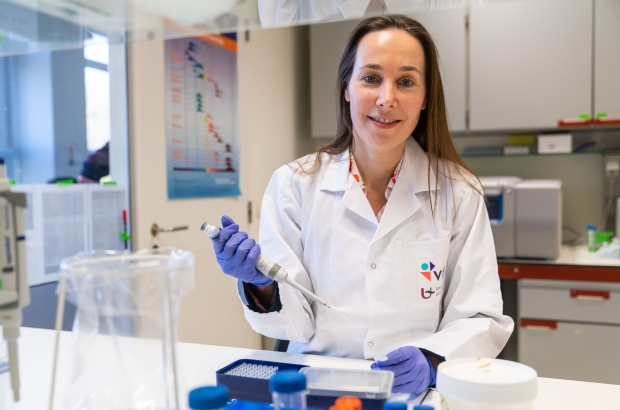

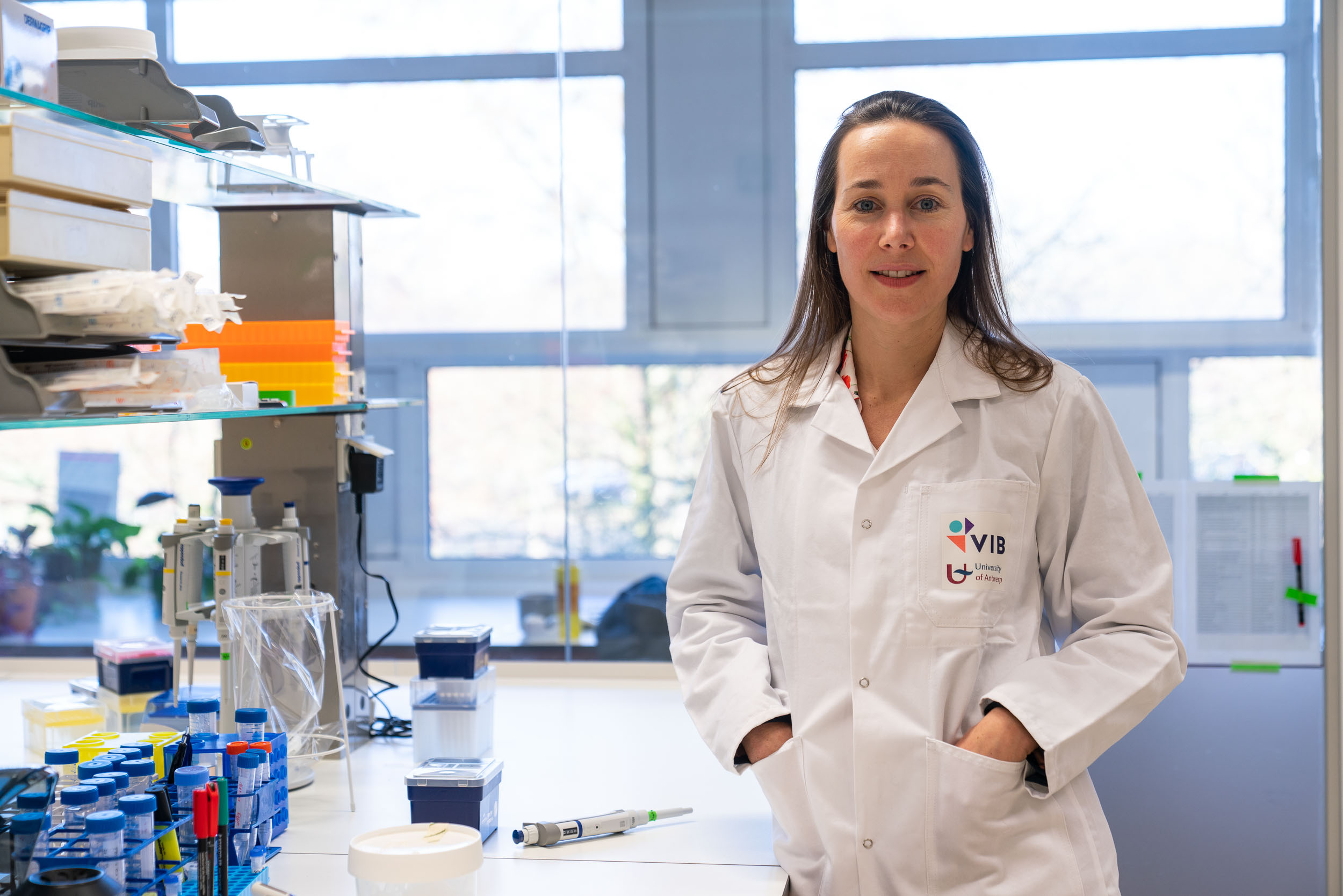

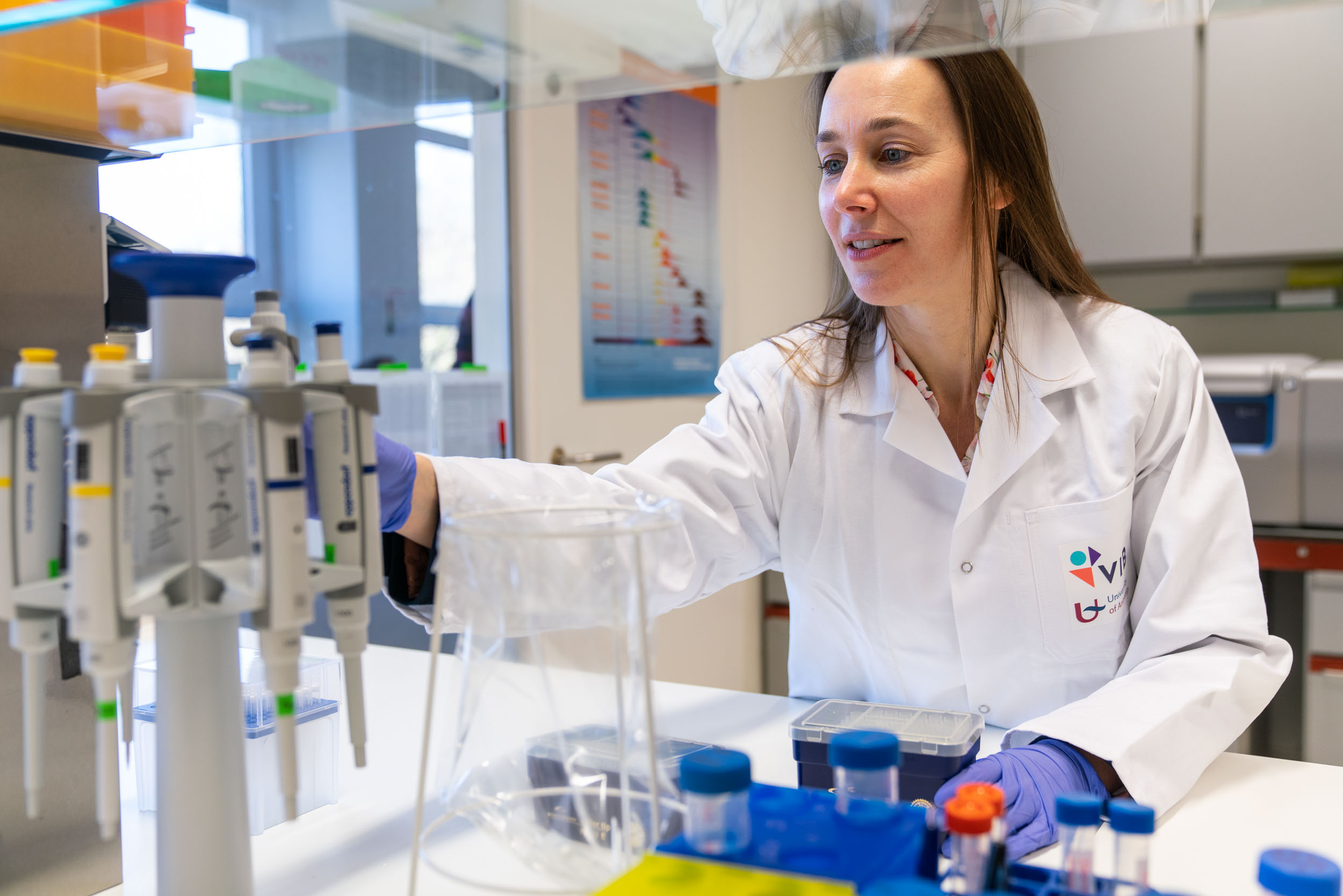

Antwerp scientist wins €1m Generet Prize

Antwerp geneticist Rosa Rademakers is the winner of the prestigious Generet Prize for Rare Diseases. At 43, she’s the youngest recipient of the €1 million award, managed by the philanthropic King Baudouin Foundation. After 14 years at the Mayo Clinic in the US – she was its youngest-ever professor – she now directs the VIB-UAntwerp Center for Molecular Neurology, where she was once a student.

Professor Rademakers heads a team specialising in frontotemporal dementia (FTD), an early-onset form of the disease that is rare but devastating, affecting people under 65 and sometimes in their 30s and 40s. The team’s research aims to identify the genetic component of this dementia for earlier diagnosis and better treatment. An enthusiastic communicator, passionate about her research and about balancing her career with motherhood, Rademakers has won recognition for her international networking as well as her prodigious career.

Why did you specialise in dementia?

It was because of my mentor Christine Van Broeckhoven, who was an expert in genetics and happened to work in dementia. At the time I would have been happy being an expert in anything. But FTD has such an effect on young people and on the whole family. I’m part of the Medical Advisory Committee of the Association for Frontotemporal Dementia in America. They have flyers for family members of patients, specifically for teenagers with a parent suffering from dementia. They want to understand why their father was an active man two years ago, going to work every day, and now he’s lying all day on the couch watching TV. And if they ask what the problem is, he’ll reply, “what do you mean, there’s nothing wrong with me”. This is because this form of dementia is accompanied by a lack of insight. There are also people about to retire with plans for their future, it’s so sad. Most people die 7-10 years after disease onset. Dementia when you’re 80 is bad, but people have had full lives by then, this is still different. So over the years, I’ve seen these patients and it’s made me extra motivated to find something to help.

What was your reaction to winning such a significant award at a relatively young age?

This is a special prize as you usually get it for your whole career. It feels good to get the recognition and it’s also exciting for the entire team and for the research aspect since we will be able to start new studies. My career has been very fast, partly because I went to the US where they give people more opportunities. I got a post-doctoral fellowship to work on a research project in Belgium, but I applied specifically to go abroad for one of the three years. When I was there, we found the gene I had been looking for in my PhD. My boss left and the Mayo Clinic wanted someone in genetic research to take over the lab and continue the work. It was also important for the clinicians that they had someone to work with to offer research opportunities to patients. Having different mentors in Antwerp and the US helped as they each had their own ways of doing things. The US is also more goal-orientated. After you’ve written your research, you choose which journal to send it to for publication and peer review. My American colleagues always go for the best, while European ones with the same data wouldn’t do that. I’d say to them, you have to believe in yourself, don’t be afraid, just try it. You’re worth it!

How will the prize money help advance your research?

We’re making progress with the research. Even though there’s no cure, we’re beginning to learn much more about the brain and how it functions. In FTD, which affects 10%-20% of dementia patients, there’s a significant genetic component (in 40-60% of patients). This award focuses on identifying a genetic cause in a form of FTD with a different protein in the brain, which is not inherited in families and is so rare that it was difficult to get enough patients together to carry out the research. We’ve finally collected enough samples and with new advances in technologies we can now look at the whole genome.

One of our hypotheses is that something happens in the patients’ brain cells during their life, in which case it is not transferred to the next generation. This hasn’t been shown for dementia but we think it could potentially explain the disease. So with this money we are going to use the newest sequencing technology to see whether there’s a genetic component or not. We’ll also look at the disease protein in the brain. We’ll find out what exactly is going wrong so that even if there are no genetic factors, we can still find therapies to try and fix it. It’s a dual approach and it’s really exciting because we’re going to get answers.

The brain is one of the most complex organs in the body. You can take out a cancer and study it, but with the brain, you look at what’s left after the person has died when the most affected brain cells are no longer there. FTD affects younger patients with dementia, sometimes in their 30s and 40s. The problem of diagnosis is that they’re often psychiatric patients first because they’ve started behaving inappropriately, such as having extra-marital affairs. They don’t realise what’s appropriate or normal, which makes it really hard.

How does your team in Antwerp work with other scientists, in Belgium and abroad?

As geneticists, we rely heavily on samples and we’re grateful that patients supply them, but the main way we get them is through clinical colleagues and brain banks. The networks I’ve set up are a large part of my success as people are willing to share samples with me, which is quite rare. I write to collaborators and I share the results and acknowledge them. If you put a lot of effort into collecting these samples, then it’s only fair. We’ve also collaborated with people who have specific expertise in areas such as biology. People are happy to contribute and have a shared publication. I still have a 5% appointment at the Mayo Clinic and I really value the connections there. Moreover, VIB, the institute where I am now, is internationally oriented.

It was recently International Women’s Day. Do you have any messages for girls interested in a career in science?

There’s enough girls starting in science and girls do just as well as men, but the American vs European way of looking at things also applies to women. When I was in the US, the head of the Alzheimer’s Association said that when it came to asking for grant funding, men would always ask for $250,000, which was the maximum, while women would ask for $200,000 on average. This is a problem! Women have to believe in themselves because they’re at least as good as the guys. I know my predecessors had to fight for everything, but that’s no longer the case, and I don’t feel that I’ve suffered any disadvantages. But it’s not easy as a mum. I’ve always wanted to be a good mum as well, putting the children to bed every night, being there for dinner. My husband doesn’t work, so that helps a lot, but I’m still involved in lots of things at home. You have to figure out how you deal with your own personal life. The fact that we don’t have all these women in high positions yet is also partly because some don’t choose to go there.

Photos: © UAntwerpen - Jasper Léonard