- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

From the archives (January 1966): The Bulletin meets René Magritte

From The Bulletin, 28 January 1966

René Magritte, born in Lessines, Belgium 67 years ago, is the last of the faithful. He has alone kept the great tradition of surrealist painting alive in our age, and is generally acknowledged to be one of the greatest of the surrealists in any case.

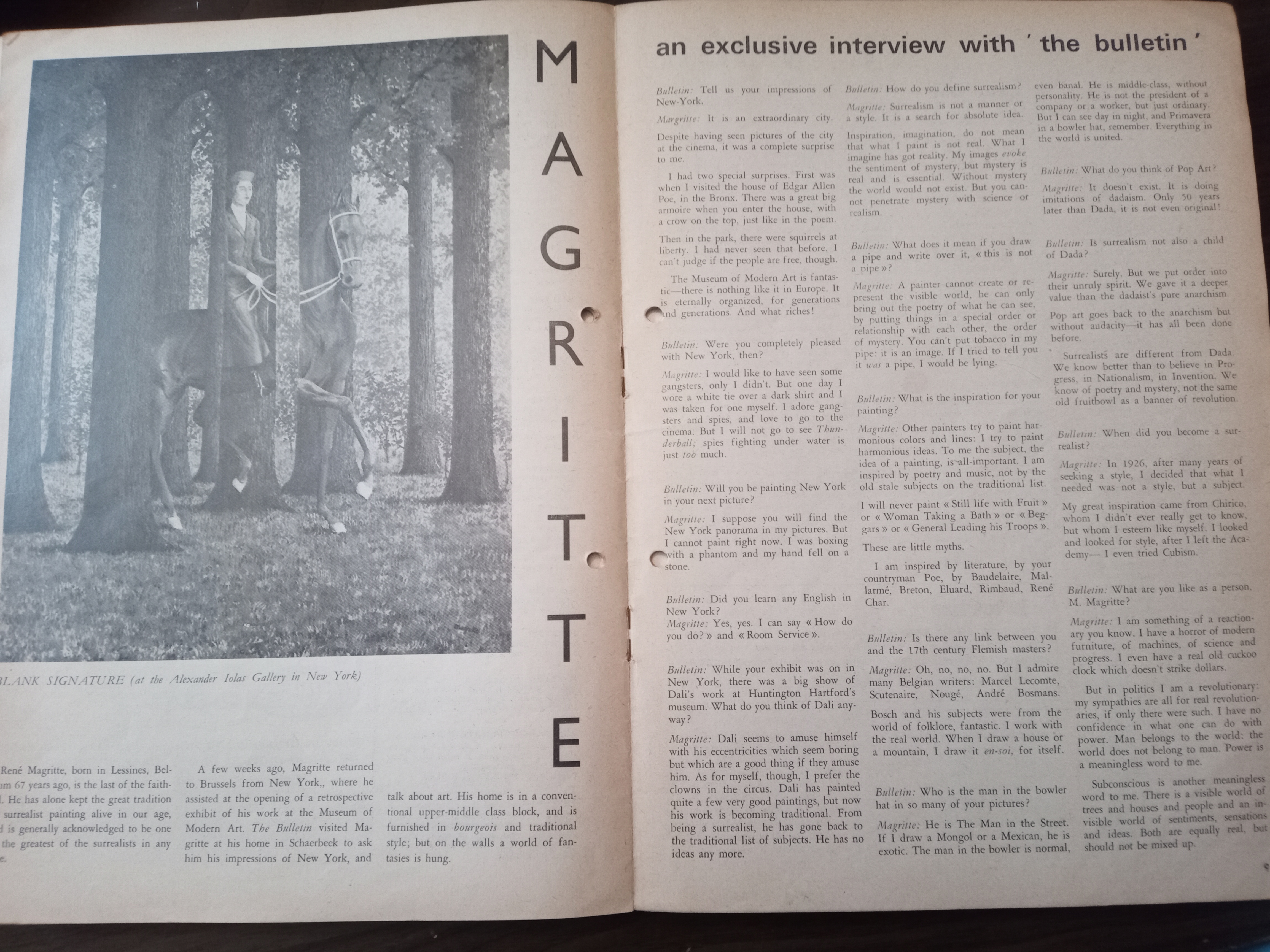

A few weeks ago, Magritte returned to Brussels from New York, where he assisted at the opening of a retrospective exhibit of his work at the Museum of Modern Art. The Bulletin visited Magritte at his home in Schaerbeek to ask him his impressions of New York, and talk about art. His home is a conventional upper-middle class block, and is furnished in bourgeois and traditional style; but on the walls a world of fantasies is hung.

The Bulletin: Tell us your impressions of New York

Magritte: It is an extraordinary city. Despite having seen pictures of the city at the cinema, it was a complete surprise to me.

I had two special surprises. First was when I visited the house of Edgar Allan Poe, in the Bronx. There was a great big armoire when you enter the house, with a crow on the top, just like in the poem.

Then in the park, there were squirrels at liberty. I had never seen that before. I can't judge if the people are free, though.

The Museum of Modern Art is fantastic - there is nothing like it in Europe. It is eternally organised, for generations and generations. And what riches!

Were you completely pleased with New York, then?

I would like to have seen some gangsters, only I didn't. But one day I wore a white tie over a dark shirt and I was taken for one myself. I adore gangsters and spies, and love to go to the cinema. But I will not go to see Thunderball; spies fighting under water is just too much.

Will you be painting New York in your next picture?

I suppose you will find the New York panorama in my pictures. But I cannot paint right now. I was boxing with a phantom and my hand fell on a stone.

Did you learn any English in New York?

Yes, yes. I can say "How do you do?" and "Room service".

While your exhibit was on in New York, there was a big show of Dali's work at Huntington Hartford's museum. What do you think of Dali anyway?

Dali seems to amuse himself with his eccentricities which seem boring but which are a good thing if they amuse him. As for myself, though, I prefer the clowns in the circus. Dali has painted quite a few very good paintings, but now his work is becoming traditional. From being a surrealist, he has gone back to the traditional list of subjects. He has no ideas any more.

How do you define surrealism?

Surrealism is not a manner or a style. It is a search for absolute idea.

Inspiration, imagination, do not mean that what I paint is not real. What I imagine has got reality. My images evoke the sentiment of mystery, but mystery is real and is essential. Without mystery the world would not exist. But you cannot penetrate mystery with science or realism.

What does it mean if you draw a pipe and write over it, "this is not a pipe"?

A painter cannot create or represent the visible world, he can only bring out the poetry of what he can see, by putting things in a special order or relationship with each other, the order of mystery. You can't put tobacco in my pipe: it is an image. If I tried to tell you it was a pipe, I would be lying.

What is the inspiration for your painting?

Other painters try to paint harmonious colours and lines: I try to paint harmonious ideas. To me the subject, the idea of a painting, is all-important. I am inspired by poetry and music, not by the old stale subjects on the traditional list.

I will never paint "Still life with Fruit" or "Woman Taking a Bath" or "Beggars" or "General Leading his Troops". These are little myths.

I am inspired by literature, by your countryman Poe, by Beaudelaire, Mallarmé, Breton, Eluard, Rimbaud, René Char.

Is there any link between you and the 17th century Flemish masters?

Oh, no, no, no. But I admire many Belgian writers: Marcel Lecomte, Scutenaire, Nougé, André Bosmans.

Bosch and his subjects were from the world of folklore, fantastic. I work with the real world. When I draw a house or a mountain, I draw it en-soi, for itself.

Who is the man in the bowler hat in so many of your pictures?

He is The Man in the Street. If I draw a Mongol or a Mexican, he is exotic. The man in the bowler is normal, even banal. He is middle-class, without personality. He is not the president of the company or a worker, but just ordinary. But I can see day in night, and Primavera in a bowler hat, remember. Everything in the world is united.

What do you think of Pop Art?

It doesn't exist. It is doing imitations of dadaism. Only 50 years later than Dada, it is not even original!

Is surrealism not also a child of Dada?

Surely. But we put order into their unruly spirit. We gave it a deeper value than the dadaist's pure anarchism. Pop art goes back to the anarchism but without audacity - it has all been done before.

Surrealists are different from Dada. We know better than to believe in Progress, in Nationalism, in Invention. We know of poetry and mystery, not the same old fruitbowl as a banner of revolution.

When did you become a surrealist?

In 1926, after many years of seeking a style, I decided that what I needed was not a style, but a subject.

My great inspiration came from Chirico, whom I didn't ever really get to know, but whom I esteem like myself. I looked and looked for style, after I left the Academy - I even Cubism.

What are you like as a person, M. Magritte?

I am something of a reactionary you know. I have a horror of modern furniture, of machines, of science and progress. I even have a real old cuckoo clock which doesn't strike dollars.

But in politics I am a revolutionary: my sympathies are all for real revolutionaries, if only there were such. I have no confidence in what one can do with power. Man belongs to the world: the world does not belong to man. Power is a meaningless word to me.

Subconscious is another meaningless word to me. There is a visible world of trees and houses and people and an invisible world of sentiments, sensations and ideas. Both are equally real, but should not be mixed up.

The Bulletin will be publishing more highlights from its extensive archive throughout 2022, as we celebrate our 60th anniversary. This article appeared in the 28 January 1966 edition of The Bulletin, which cost seven francs.