- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

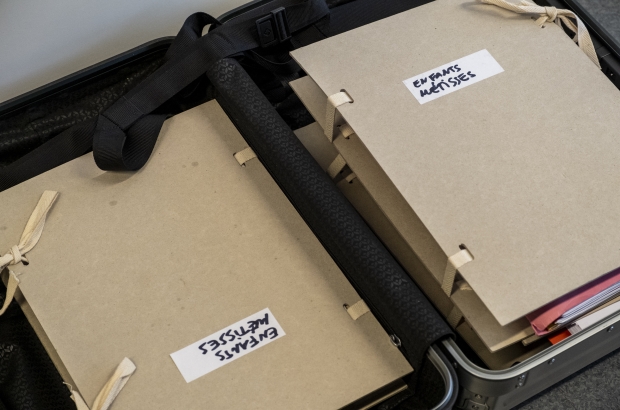

Belgian state guilty of crimes against humanity for treatment of mixed-race Congolese children

The Belgian state has been found guilty of crimes against humanity in a case brought by five mixed-race women abducted from their families at a time when the Congo was a Belgian colony.

While the case was dismissed at first instance, the Brussels Court of Appeal has now recognised the claimants' loss and ordered the state to compensate them.

“It's a victory, a historic judgement,” said Michèle Hirsch, the lawyer who led the case.

The Court of Appeal said in its ruling that it had been established that the five women "were taken from their respective mothers, without their consent, before the age of seven, by the Belgian state in execution of a plan for the systematic search for and abduction of children born to a black mother and a white father, raised by their mother in the Belgian Congo, solely on the basis of their origins".

The Brussels Court of Appeal described these abductions as "inhuman acts and persecution constituting a crime against humanity under the principles of international law".

The court also ordered the Belgian state to pay €50,000 in compensation for the non-pecuniary damage suffered by the claimants as a result of "the loss of their link with their mother and the damage to their identity and their link with their environment of origin".

“This is a landmark ruling by the Brussels Court of Appeal,” Hirsch said. “It is the first time in Belgium, and probably in Europe, that a court has convicted the Belgian colonial state of a crime against humanity.”

The five women - Simone Ngalula, Monique Bitu Bingi, Léa Tavares Mujinga, Noelle Verbeeken and Marie-José Loshi - who were born in the Congo between 1945 and 1950, celebrated the historic ruling.

"We shouted, we applauded and we jumped," said Léa Tavares Mujinga. “It was a relief after a sleepless night.”

Monique Bitu said “a weight has been lifted” and Noelle Verbeken noted that “the Belgian state has finally done us justice. This decision says that we have a certain value in this world. We are recognised.”

When the women were children in the Belgian Congo, they were regarded, like all other mixed-race children, as children of shame and sin.

Between 1948 and 1961, orders were given to take mixed-race children away from their families as soon as possible and entrust them to religious institutions. The process was so haphazard that victims were left unable to trace their relatives – their names were changed and they were moved to other parts of the country.

When the Congo became independent, the religious institutions where these abducted children lived were closed. Some children were sent to Belgium for adoption, while others were abandoned to their fate.

“When the [institution closed], we were abandoned,” recalled Léa Tavares Mujinga. “I was more than 1,000km from my mother, abandoned in the street, with nothing.”

In 2019, then-prime minister Charles Michel gave a verbal apology on behalf of Belgium during a plenary session in parliament.

The legal battle for the five women in the court case began soon after, with the first rejection coming in 2021 when a court said the state-sanctioned abductions could be considered crimes against humanity today, but not during colonial times. The Brussels Court of Appeal rejected this view.

When asked for his reaction, prime minister Alexander De Croo declined to comment. The new foreign affairs minister Bernard Quintin took note of the ruling and announced that he would examine it "very carefully".

But Marie-Colline Leroy, secretary of state for equal opportunities, underlined the judicial decision as sending out "a strong signal".

“The Court of Appeal recognises the need for reparations for the victims of colonialism and systemic racism implemented by Belgium in the Congo,” said Leroy.

“This is an essential step towards healing the wounds of the past and moving forward towards a fairer society. It is up to us, as politicians, to continue this work, which is not limited to remembering, but assumes responsibility and gives consideration to reparations.”

African Futures Lab and Amnesty International both congratulated “this courageous decision which opens the way to full recognition of the atrocities committed during colonisation and their continuing harmful effects on the lives of the survivors and their descendants”.

The ruling could set a precedent. The number of mixed-race children who were victims of the Belgian policy is generally estimated at between 15,000 and 20,000.