- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

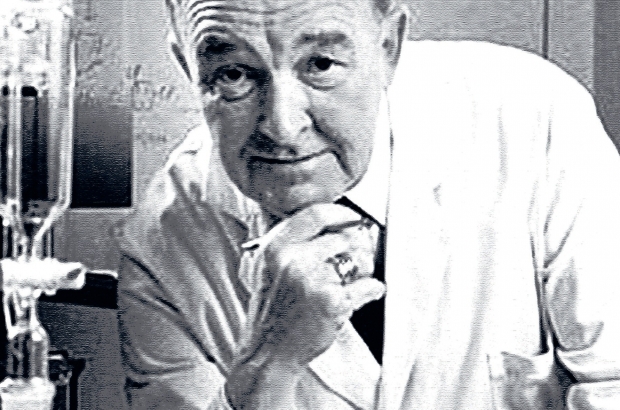

The Brand – Janssen Pharmaceutica

From tiny atoms do mighty multinationals grow. We explore the medical legacy of the visionary Dr Paul Janssen

Janssen’s multi-billion-dollar story starts with Dr Paul in Turnhout, about 60 years ago. Paul Janssen studied in Namur, Leuven and the US, and graduated as a medical doctor from Ghent University in 1951. But instead of following the academic route, Dr Paul set up his own research lab where he created chemical compounds and tested their medicinal effects. Legend has it that Dr Paul inherited his entrepreneurial flair from his father, a general practitioner-cum-wholesaler of imported medicines.

After just a couple of years, Dr Paul marketed his first molecule under the brand name Neomeritine—a drug against premenstrual pain that is still on the market today. His lab was soon churning out one active molecule after the other, which Dr Paul licensed to other companies in charge of manufacturing and distributing the drug.

But he soon realised it would be more profitable to produce these drugs himself, and decided to build manufacturing facilities. In 1957, he bought a 65-hectare plot of land from the town of Beerse for $1 per square metre, on the condition that he expand and hire 100 people in five years. Naysayers thought he was crazy to make the commitment, but the company grew and had hired about 200 people by 1960.

When US company Johnson & Johnson said it was interested in buying Janssen, Dr Paul jumped on the opportunity and sold the company’s assets in 1961, in return for shares. “Dr Paul was visionary,” says Stefan Gijssels, Janssen’s vice-president for communications and public affairs in Europe, the Middle East and Africa. “He understood that in this global environment he needed financial back-up to expand and fulfil his ambitions. Plus it gave the company and its employees the ability to fall back on the Johnson & Johnson structure in case anything happened.” Under Johnson & Johnson’s umbrella, Janssen added more successful molecules to its portfolio – drugs that often transformed entire medical fields.

For example, haloperidol is an antipsychotic drug sold under the commercial name Haldol. It was initially used to treat schizophrenic patients, at a time where straitjackets and electric shocks were the only available remedies. Also in the 1960s, Janssen released fentanyl, a painkiller about 100 times more powerful than morphine, which is still widely used today as an anaesthetic for surgery, or to relieve pain in terminal patients. Last but not least, Janssen has developed gastro-intestinal drugs that have become household names, including Imodium and Motilium.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Janssen continued its international expansion and opened research centres in France, Germany, Spain and the UK, as well as branches in the US and China. When he found out that Chinese manufacturers were copying Janssen’s medicines, Dr Paul offered them the chance to work together rather than suing them. Gijssels says: “We were one of the first pharmaceutical companies in the world to have a real joint venture agreement with the Chinese authorities.” In addition to a manufacturing plant in Xian, opened in 1985, Janssen now runs R&D facilities in Shanghai and Mumbai, India.

Dr Paul retired in 1994, at the age of 68. But he kept working in the lab – in particular, he was busy concocting a one-a-day Aids pill. And he eventually made it: rilpivirine was approved for sale last year under the commercial name Edurant, almost eight years after Dr Paul’s death in 2003. But between Dr Paul’s gung-ho beginnings and the posthumous release of this Aids treatment, the pharmaceutical world has completely changed. Whereas in the 1950s a drug could be launched on the market just a year or two after the molecule had been synthesised, the development of a drug can now easily stretch over 10 years.

“Twenty years ago you developed a drug, invested in it, then it reached the market after, say, seven years and you had another 13 years before the patent expiry where you could make good money from the drug,” Gijssels recalls. “Now you have less time on the market, so the price of the drug goes up to recoup the investment costs. The cost of research increases but the chance of having a drug approved decreases because the efficacy and safety demands are increasingly high.” In some pharmaceutical areas such as antibiotics, research investments are already dwindling because many companies find that the spending is not worth it, Gijssels warns.

“The political environment doesn’t always understand that our drugs sales lead to more research,” he says. Some solutions have emerged, though, such as fast-track approval procedures for certain drugs with an immediate medical need, like HIV treatment. Despite this high-pressure environment, Janssen decided to go for high-risk research. “In the past we tended to stay in our comfort zone, looking at diseases of which we already knew the biochemical mechanisms quite well. But now we take the high jump.” The company will research diseases that are less well known, but for which a scientific solution is critical, such as Alzheimer’s disease. Other conditions such as obesity will be less of a priority for the company, because the best solution lies in prevention rather than science.

Janssen decided to focus its research on five priority areas: neurological diseases such as schizophrenia or dementia; infectious diseases such as HIV/Aids, Hepatitis C or tuberculosis; cancer, in particular multiple myeloma and prostate cancer; immunology; and metabolism, including diabetes. If that strategy pays off, the resulting drugs can potentially conquer large, empty markets, have a huge impact on patients’ lives and bring big benefits to the company.

Gijssels’ tasks include trying to improve the industry’s image. “This is a subject that continues to frustrate me,” said Jane Griffiths, company group chairwoman for Janssen Europe, Middle East and Africa. “The industry needs to be more proactive in communicating about the changes it is making, to become more transparent. There is so much positive work going on, and we need to get better at ensuring people are informed about these activities.” Gijssels agrees: “We have a gigantic impact on people’s lives, but it’s like the work of angels – no one sees it. The pharmaceutical industry deserves more credit for its discoveries, and for the financial risk that it absorbs.”

But he adds that Belgium is the country in Europe where the general public has the highest opinion of big pharma. According to a survey carried out every two years by the European chemistry lobby Cefic, 84 percent of Belgians have a favourable opinion of the pharmaceutical industry – up from about 76 percent in 2000, and about 18 percentage points above the EU average. “This is the result of major communications investment, of having the company’s boss in the press, of talking about the industry’s contribution to the country’s economy,” Gijssels says proudly.

JANSSEN IN BELGIUM

Belgium is an essential part of Janssen’s – and Johnson & Johnson’s—global operations. In addition to its historical research and production centre on its Beerse campus, the group runs a chemical production plant in Geel and international distribution facilities in Courcelles and La Louvière, as well as the Johnson & Johnson European headquarters near Zaventem airport.

Every penny spent by the group goes through the global treasury services in Belgium. “We’ve had lots of discussions with the Belgian authorities and got some important tax breaks,” says Stefan Gijssels, vice-president for communications and public affairs for Janssen Europe, the Middle East and Africa. “We work with them to make sure Belgium remains an attractive environment, and that’s one of the reasons why we continue to invest here. All our new drugs are manufactured in the country.” According to Gijssels, Belgium has convincing assets to attract foreign scientists. “Belgium is welcoming: the quality of life is good here, people speak English, there are good international schools and lots of work opportunities for spouses,” he says.

In 2007 and 2009, Janssen had to face the global economic crisis and two of its blockbuster products going off-patent at about the same time. The company cut about 600 jobs in Belgium at that time, but things are looking brighter today, as Janssen has recently advertised about 120 job vacancies.

FACTS AND FIGURES

• Janssen has been part of Johnson & Johnson, one of the largest healthcare groups in the world, since 1961

• In the past two years, Janssen has dropped the names of its subsidiaries, such as HIV drugs company Tibotec, and regrouped them under the Janssen name

• Janssen employs about 5,000 people in Belgium – including 1,500 in R&D – out of about 40,000 employees worldwide

• Janssen invests about 20% of its turnover in R&D activities worldwide