- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Brussels expands its successful ‘museum prescriptions’ programme beyond mental health patients

The city of Brussels is expanding its innovative programme offering museum visits on prescription for people suffering from anxiety, stress, depression.

Following the “entirely positive” results of the museum prescriptions pilot scheme launched in September 2022, a second phase of the art and health project is being rolled out from 1 June.

Free access to museums will be extended to users of other health services such as neurology, cardiology and revalidation, as well as cancer sufferers and people living with Alzheimer’s.

In addition to improving access to culture for disadvantaged groups, the programme aims to give the medical sector a therapeutic tool that is complementary to traditional therapies.

The cultural experiences available have increased with 14 museum partners now involved in the scheme. Joining the initial five city museums providing tours of sites as varied as the old sewer network, lace-making tradition and the wardrobe of the Manneken Pis, are landmark institutions Bozar, the Magritte Museum and Design Museum Brussels.

The number of prescribers has also grown to 18 medical facilities with a range of professionals offering patients the opportunity to visit exhibitions or take a guided tour. Beneficiaries can invite a family member, friend or carer to accompany them.

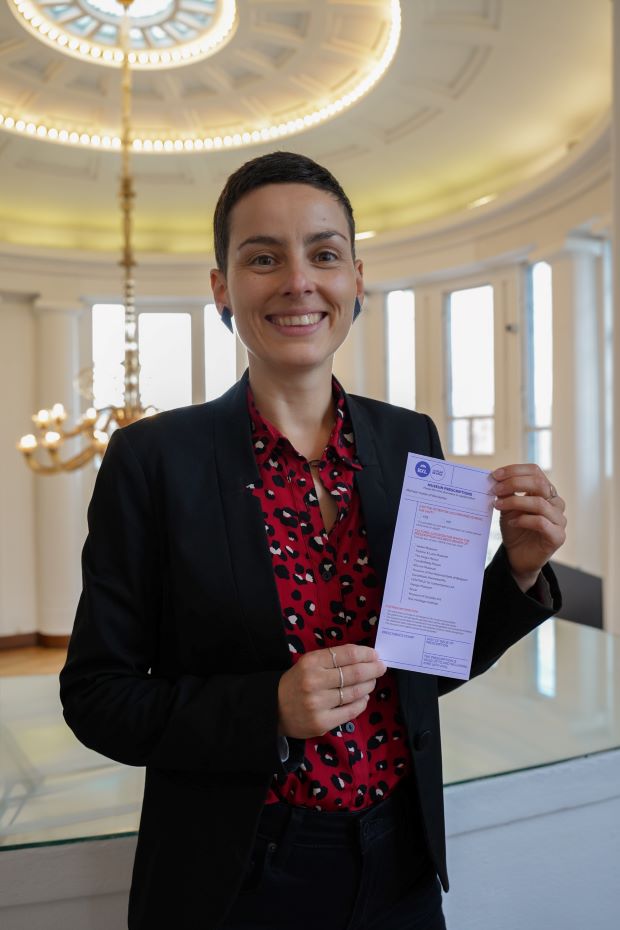

Brussels deputy mayor and culture alderwoman Delphine Houba (pictured) teamed up with the psychiatry service of Brussels hospital CHU Brugmann to set up the initiative. While her inspiration came from a similar project in Montreal, the sharp rise in psychological disorders following Covid lockdowns reinforced her determination to come up with a more holistic approach to patient care.

“For people who have never dared open the door of a museum, these visits can be part of the healing process,” she told The Bulletin.

Having once chaired the board of Brugmann hospital, the city socialist politician is delighted by the pilot project’s success. “We’re very proud. In politics, you have ideas and sometimes they fail. Here, I took the risk and there’s been a 100% positive response.”

Houba is pleased to see “prestigious” partners like Bozar, the Fine-Arts Museum and other institutions signing up for the programme. Could it be extended in the future to offer access to theatre, performance and cinema? “One of the keys to the success has been that it was simple to put in place, especially as hospitals and the medical sector are already administratively busy,” she explains. “Museums are also permanently open, but why not include dance, music and film one day, that would be superb.”

Brugmann’s head of clinics Dr Catherine Hanak has observed numerous beneficial effects from participating patients, including increased feelings of relaxation, well-being and energy and reduced stress and anxiety. The museum experiences sparked a process of recompensation that was similar to the dopamine secreted by addictive pursuits, she explained.

One beneficiary, Sophie, 32, made a trip to the Brussels City Museum. “It was very interesting. The visit took my mind off my worries,” she said.

Combatting self-stigmatisation and social isolation are also positive effects of the cultural outings. Another patient, Saïd, 52, admitted that he had never dared to visit a museum before. He asked Dr Hanak: “Could you advise me what I should wear? Can you explain how I should behave?”

For the psychiatrist, the project was a pleasure for medical practitioners as well as an additional tool for patients who were advancing with their recovery. “We rarely have the opportunity to do something very concrete that improves their condition immediately and tangibly, without any adverse effects.”

An increasing number of scientific papers were showing the link between art and health, pointed out Dr Hanak. This latest initiative was an extension to the art and music workshops that were an important part of the therapy offered by psychiatric services. “They help patients reconnect with their environment, escape their suffering and explore the outside world. That’s where the project of the city of Brussels fits in.”

It also created a new role for museums, and one that was attracting international attention. In addition to Montreal, Lithuania and Valencia in Spain were developing similar projects, said Dr Hanak, who added: “It would be magnificent, if it spread to other regions [in Belgium]”. In an ideal world, everyone with a health problem would have free access to culture, she insisted.

One medical facility now issuing prescriptions is the nonprofit group BAOB which accompanies cancer sufferers. Its president Juliette Berguet shared the experience of members, many of whom were single mothers. They welcomed the valourising experience of stepping outside their comfort zone and encouraging their own artistic efforts. “We all have talents ourselves, and this helps us in our reconstruction and in taking a place in society.”

Partner museums equally welcomed the initiative. Bozar director Christophe Slagmuylder said the arts centre was already active in the domain of arts and wellbeing. “We hope to put in place training for staff to improve their interaction with mental health communities to create more inclusive spaces.”

For Design Museum Brussels, the project was a new tool that gave sense to the Atomium site’s practice, said Terry Scott, responsible for audience development and engagement. “We are rethinking our cultural offer. As well as museum visits, we also propose visits with mediation, which touch on memory for example for Alzheimer’s patients.”

Among the scheme’s partner medical facilities are hospitals, mental health, medical and family planning centres. Prescribing practitioners include psychologists, social workers, GPs, occupational therapists, nurses and physiotherapists. Posters and leaflets with information about the programme are being distributed in medical waiting rooms across the city.

Photos: ©City of Brussels