- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

The Bulletin at 60: From the archive (2003): Jacques the lad, profile of Belgian hero Brel

On October 9, 1978, France woke up to some sad news: singer-songwriter Jacques Brel had died of a pulmonary embolism at a hospital near Paris. His cancer had been common knowledge for years, but the whole nation went into shock. I was a child at the time, but I still remember the mournful short films that TV channels broadcast again and again after his death with one of his last songs, Orly.

Twenty-five years after Brel’s arrival in Paris, the singer had become something of an icon in his adoptive country. People had grown to love this emaciated man who sang strange songs of anger and despair. Now, another quarter of a century later, he’s as much part of French culture as Maupassant and Brassens. Dozens of schools and streets are named after him, and his songs are on the syllabus for national literature exams. Some people even think he was French.

Brel did have an ambiguous attitude to his native country: he named one of his daughters France, read Le Monde rather than Le Soir, abused his fellow Belgians in interviews and even cracked jokes at their expense (“What do you call an intelligent Belgian? Swiss!” was one of his favourites).

Yet deep down, he was as Belgian as anyone can be. Some have traced his surname back to Bruegel: the truth of that may might be disputable, but no one can deny the echoes between some of his songs (like the four tableaux of Le Plat pays) and the placid landscapes and lowering skies conjured up by that Flemish painter. His songs abound with vivid evocations of Place De Brouckère, Knokke-Le-Zoute, Liège in the snow, the towers of Bruges and Ghent and mussels and frites.

In the words of his biographer Olivier Todd, “Belgium haunted Brel long after he stopped living there.”

Brel was born in Schaerbeek on 8 April 1929, into a middle-class francophone family. Early photos show him grinning in his shorts, his hair neatly combed, with his brother Pierre, five-and-a-half years his senior, by his side. He led a quite life (which he later described as dull) surviving on food rations during the German occupation, spending holidays at the coast and frequenting a scout club where he gained a reputation as an entertainer. School (he attended the Institut Saint-Louis near the Botanique) was never his forte. He preferred writing short stories and composing songs, which he sang, strumming a guitar.

At 18, he started work at Vanneste & Brel, the family company, which manufactured cardboard packaging. He spent much of his time at La Franche Cordée, a Catholic youth club where he mingled with well-to-do, idealistic people of his age. That’s where he met Thérèse Michielson, better known as Miche, a pretty blonde girl with bright blue eyes and a turned up nose. Before he knew it, he was married and living in a terraced house in Dilbeek, and was the father of a little girl, Chantal.

But Brel couldn’t settle. He always saw himself as a nomad and, increasingly irked by his comfortable lifestyle and hoping to further his singing career (he’d made timid beginnings under the pseudonym Jacques Berel), he decided to try his luck in Paris. Leaving his wife and child, he boarded a train in June 1953.

This was the golden age of chanson in Paris – Brassens, Ferré and Bécaud were all the rage – but the city gave the naïve young Belgian a cool welcome. Cabaret owners frowned when they saw him arrive, a gawky figure with a bad moustache and worse teeth. One record label executive to who he showed his songs remarked “you’re not thinking of singing those yourself – look at you!” And the songs, all starry-eyed idealism, angels and brotherly love, rubbed Parisians the wrong way. One reviewer cruelly pointed out that “there were excellent trains from Paris to Brussels”. Brel wrote to his wife that he felt like an outsider.

Brassens who met him at the time and lent him occasional support, jokingly dubbed him “Brother Brel” – a reference to his obsession with God and the cassock-like tunic he wore. Another star of the time, Juliette Greco, never forgot their first meeting. “He was skinny and intense, with eyes that glowed like coals. He looked like a wolf.” She took him under her wing, agreeing to sing Le Diable, one of his songs.

Brel wouldn’t give up. He visited a dentist and wrote more songs. In 1956, he penned Quand on n’a que l’amour, a poignant number about the power of love over “cannons’ and “drums”, which some saw as a reference to the Budapest uprisings of that time. But it was another three years before his first real hit. Ne me quitte pas, the searing plaint of a man begging his estranged lover to let him become “the shadow of her hand, the shadow of her dog” has gone down as one of the best love songs in history, yet Brel, ironically, didn’t think it had anything to do with love, or women. “It’s about an idiot, a loser,” he said.

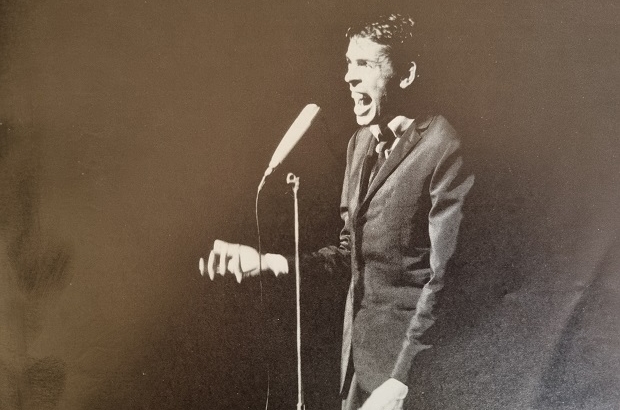

Success transformed his life into a headlong rush. A tireless performer, he toured France, Belgium, North Africa and Quebec at a frenzied pace, smoking four packets of cigarettes a day and drinking into the night with his musicians. His concerts were a unique, unforgettable experience. At a time when variety singers turned to lip-synch and fancy sets, Brel invariably appeared in a black suit, standing in a white pool of light and sweating profusely – he could lose 800 grams in one evening. He always sang live, gesticulating frantically, enacting each song as if performing it for the first or last time. He was haunted by stage fright all his life, and right up to the end of his career he would vomit before every concert.

Between 1959 and 1967, Brel spawned some of his most famous songs: Madeleine, about a man stood up every evening by the woman he loves; Amsterdam, a gritty atmospheric piece that smells of the sea; Les Flamandes, a satire on bourgeois conformity in Flanders, which ruffled a few feathers, and Les Vieux, a harrowing account of old age from 1963, which many have seen as a reference to his parents, who died within two months of each other the next year.

Flemings were not the only ones to take offence. Although he drew a large female audience, the romanticism of the early days gradually gave way to rampant misogyny in numbers like Les Filles et les chiens and Les Biches.

Backstage, too, his attitude to women verged on the callous. Although he deserted the family house and collected mistresses, he never divorced Miche and fathered two more daughters: France (who’s now in charge of the Brel Foundation), born in 1953, and Isabelle five years later. On his rare visits to Brussels, he made sure that his daughters were getting a strict education, and forbade them from wearing jeans. He had few women friends: Greco and the singer Barbara were exceptions. He called them “mecs” (“guys”), which they took as a compliment.

In 1967, he suddenly gave up performing. “I have nothing more to say,” he explained. “I don’t want to cheat.” Fans wrote to him in despair, threatening to kill themselves.

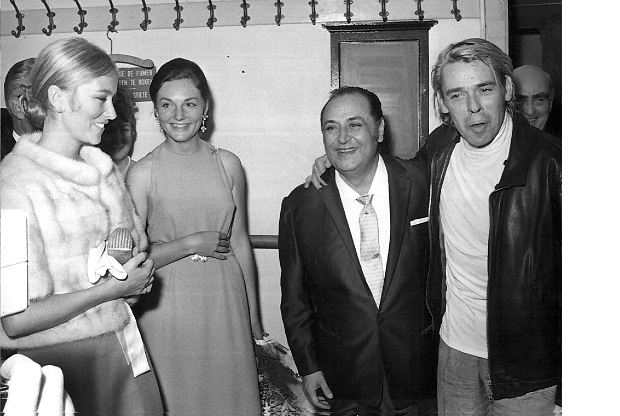

Many said it was just a publicity stunt, but his friends knew better. Brel never stepped onto a stage again, other than a stint as Don Quixote in the musical L’Homme de la Mancha (pictured above). At around the same time, another musical made his songs famous on the other side of the Atlantic: Mort Schuman’s and Eric Blau’s Jacques Brel Is Alive and Well and Living in Paris. At Miche’s insistence, Brel flew to New York to watch a performance. He was uneasy at the homage. “I feel I’m dead, a very old man,” he said.

The 1970s saw him embark on a new career in the cinema. His fans discovered a talented actor with an eerie gift for identifying with his characters: a schoolteacher accused of sexually abusing his teenage students in André Cayatte’s Les Risques du métier, a gangster in Claude Lelouch’s L’Aventure c’est l’aventure. Then came two attempts behind the camera: the promising Franz, set on the Belgian coast and starring Barbara, and Le Far West, a spectacular flop.

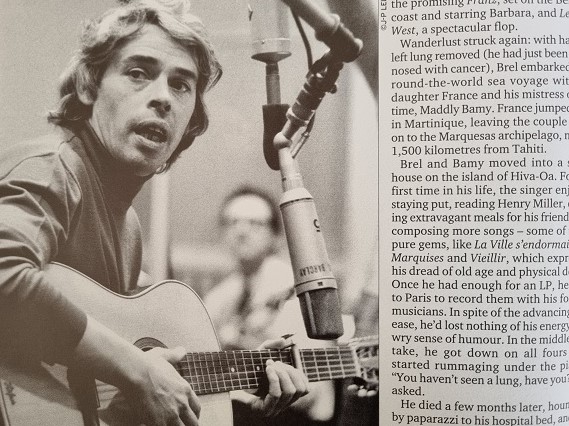

Wanderlust struck again: with half his left lung removed (he had just been diagnosed with cancer), Brel embarked on a round-the-world sea voyage with his daughter France and his mistress of the time, Maddly Bamy. France jumped ship in Martinique, leaving the couple to go on to the Marquesas archipelago, nearly 1,500 kilometres from Tahiti.

Brel and Bamy moved into a small house on the island of Hiva-Oa. For the first time in his life, the singer enjoyed staying put, reading Henry Miller, cooking extravagant meals for his friends and composing more songs – some of them pure gems, like La Ville s’endormait, Les Marquises and Vieillir, which expresses his dread of old age and physical decay. Once he had enough for a LP, he flew to Paris to record them with his former musicians. In spite of the advancing disease, he’d lost nothing of his energy and wry sense of humour. In the middle of a take, he got down on all fours and started rummaging under the piano. “You haven’t seen a lung, have you?” he asked.

He died a few months later, hounded by paparazzi to his hospital bed, and he was buried on the island of Hiva-Oa, just metres from the tomb of another great wanderer, Paul Gaugin.

This article was first published in The Bulletin on 20 March 2003.

Photos: © The Bulletin; Jacques Brel (right) at opening gala of L’Homme de la Mancha with Princess Paola of Belgium, 1968 © Belga