- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Kazerne Dossin: New portraits unveiled in unfolding story of Jewish and Roma wartime deportation

A 17-year search to uncover the missing faces of more than 25,000 Jewish and Roma detainees imprisoned by the Nazis in Belgium, is a step closer to completion.

Kazerne Dossin - Memorial, Museum and Research Centre on Holocaust and Human Rights in Mechelen, celebrates the 10th edition of its annual Portrait Ceremony by unveiling 210 new faces on its portrait wall.

The former military barracks commandeered by the Nazis during World War Two is a vibrant museum and archive centre. It commemorates and honours those who were detained and subsequently deported to the death camps.

Since the museum’s opening in 2012, archivists, historians and volunteers, together with relatives of the victims, have pored over thousands of photographs and documents in the campaign ‘Give Them A Face.’

Although records seized at Kazerne Dossin following its liberation in 1944 were incomplete - consisting largely of deportation lists and abandoned personal documents - they did include some photo ID cards.

The museum’s inception was an opportunity for curators to publicly salute the men, women and children who were arrested in Belgium and Northern France. When it opened its doors in December 2012, it wasn’t possible to visually identify four out of five victims. Today, 20,904 faces of people deported from Kazerne Dossin have emerged and are on display so that their stories will never be forgotten.

Resistance fighters risked their lives to free deportees

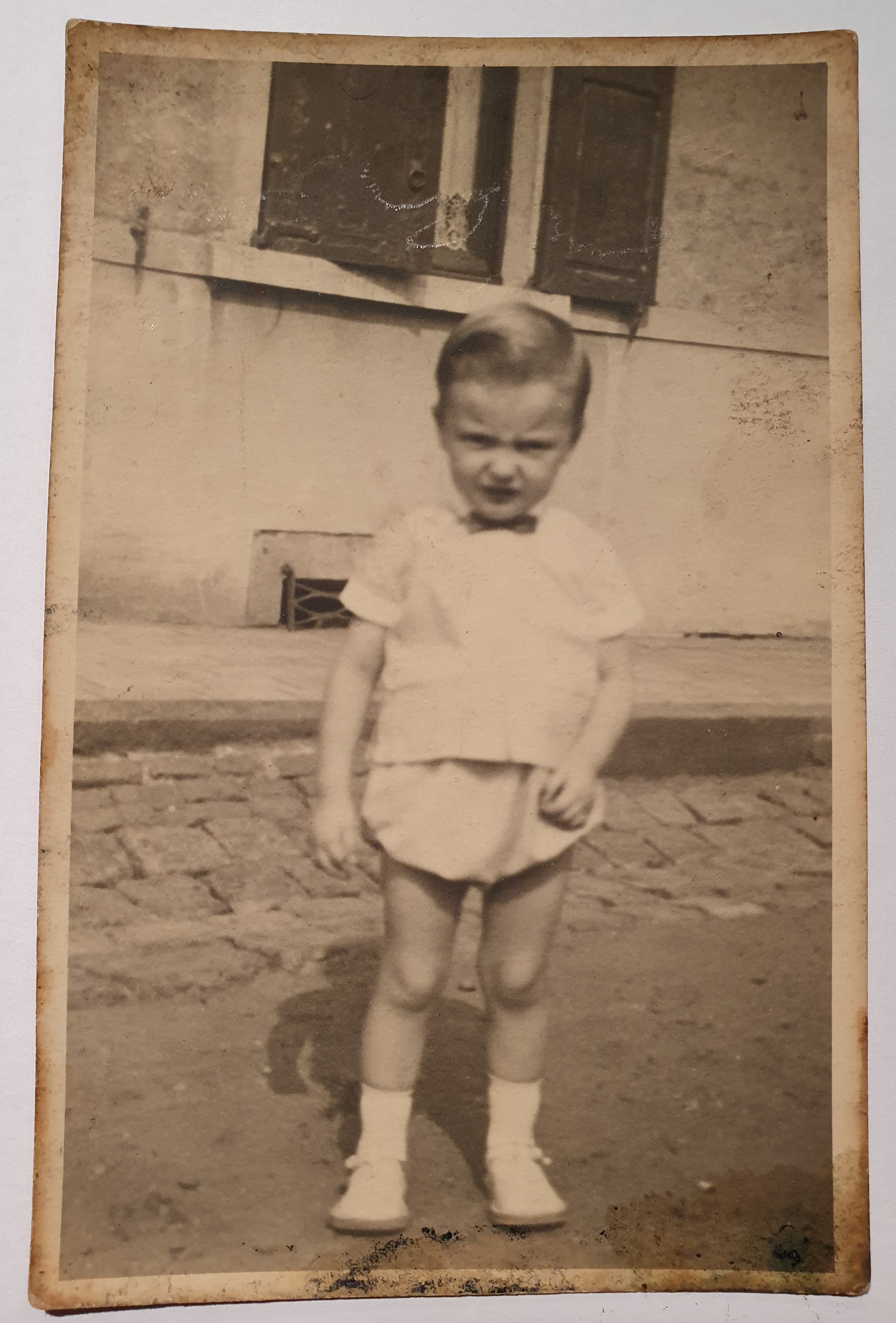

The extensive research behind the ‘Give Them a Face’ campaign has proved hugely important, as shown in the attempt to trace deportee Aron Luksenberg (pictured above as a child). He was presumed to have been murdered in the extermination camp of Auschwitz-Berkenau in 1943 after deportation from Mechelen. Jo Peeters, curator of the Huis van het Belgisch-Franse Verzet (House of the Belgian-French Resistance), scrutinised diaries, testimonies and articles published by local historians in an effort to find him. This led to firm evidence that Aron had escaped from Transport XX heading for Auschwitz, when it was held up by resistance fighters. Following his escape, he was taken to Bierbeek Abbey and then hidden in the Brabant Walloon village of Rosières. After the war, Luksenberg was adopted by a Jewish family. Although Luksenberg has since passed away, his memory, lives on.

Dorien Styven, archivist at Kazerne Dossin, told The Bulletin that the centre receives around 2,000 enquiries each year from families anxious to search for the truth about their ancestors, as well as students and researchers. She said it has been a huge collaborative effort and was pleased to announce that another 210 faces had been found this year. She said adding the faces – and therefore reading the name of each victim – brings to life the story behind each of those who were arrested and detained.

Locked in dormitories while awaiting deportation, conditions were grim, explained Styven. “There was psychological abuse, food was scarce and people were humiliated.”

The majority were Jews transiting through Belgium, as well as some members of the Roma travelling community. Many of the Jews caught in Belgium were trying to emigrate to flee persecution. They had often worked hard to earn enough money to board the Red and White Star Line ships sailing regularly from the port of Antwerp for Britain and North America.

Following their arrest, they were stripped of their identity and addressed only by their number. Escape was almost impossible as armed guards patrolled every corner of the building, 24 hours a day. Most detainees were unaware of the awful atrocity that awaited them beyond Belgium’s borders. They were thrown into railway carriages and forced to travel like cattle, bound for the death camps. The majority of those imprisoned in Mechelen - the only detention centre for Jews and Roma in Belgium during the war - were deported to Auschwitz-Berkenau in Poland.

Escape from Dossin camp may have been impossible, but three resistance workers hatched a plan to halt Transport XX in Boortmeerbeek. Last year, the Brussels parliament agreed to erect a statue in honour of the young freedom fighters who stopped the Auschwitz-bound train leaving Dossin barracks.

Robert Maistriau, Youra Livchitz and Jean Franklemon managed to open the door of a carriage and free 17 prisoners. Another 233 deportees escaped further along the journey, liberating themselves with smuggled tools, although many were recaptured and later murdered. However, 118 of them escaped and their freedom was thanks to the three brave heroes who risked their own lives to save others.

Livchitz was sentenced to death and shot by the Nazis, Maistriau was sent to a concentration camp but survived, dying in 2008. Franklemon also survived the war and became a musician, passing away in 1977.

Simon Gronowski’s story

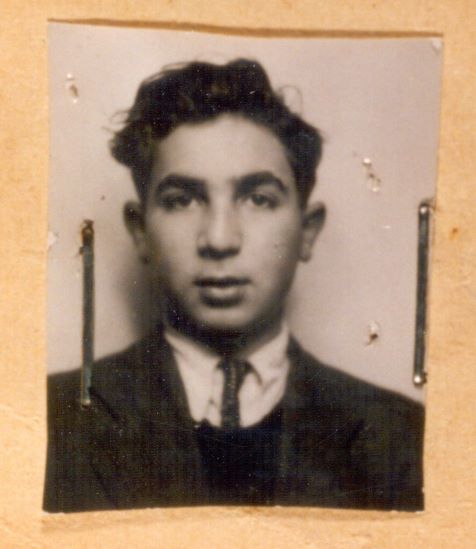

The three Resistance fighters hold a special place in the heart of 91-year-old Simon Gronowski (pictured above in 1945). On 19 April 1943, 11-year-old Gronowski and his mother Chana - who had a presentiment of their fate - boarded Transport XX at Dossin barracks headed for Auschwitz. They were among 1,630 detainees deported that day. The three resistance fighters managed to stop the train near Boortmeerbeek, using red paper and a lantern on the line to create a stop signal for the driver, who suddenly braked. A shoot-out ensued, but Gronowski’s carriage remained shut. Buoyed by the chaos, other detainees succeeded in forcing the door open a little. Gronowski’s mother seized the moment and lowered her son to the ground through a tiny gap in the carriage. Giving him a 100 franc note that she had hidden, she instructed her son to run. Tragically, she and her daughter, Ita, who was deported later, were murdered by the Nazis.

Gronowski ran through the night before knocking on the door of a house. He was taken to the local gendarme who helped him return to Brussels and reunite with his father, who was in hiding after escaping detention by being hospitalised at the time of his family’s arrest. “The man who hid me knew where I came from and did not denounce me. If he was discovered hiding a Jewish child, they would have shot him,” said Gronowski.

For 60 years, Gronowski spoke little about these harrowing events, but was asked to testify and write his story. “Since then I have been invited to Dossin and into schools in Belgium to tell my story.”

After the war, Gronowski became a lawyer and had a family of his own. He, like so many other detainees at Dossin Kazerne, managed to seek some comfort in the camp by thinking of music.

Music-themed portrait ceremony

It’s one reason why this year’s theme at the portrait unveiling was music. Seven years ago, Gronowski was introduced to the composer, Howard Moody, who wrote an opera based on the man’s miraculous escape that was performed in Boortmeerbeek shortly before the veteran’s 90th birthday.

Today, Gronowski loves nothing more than to play jazz piano. He also lifted the spirits of neighbours and passers-by during the coronavirus pandemic when he opened his windows, sat at his piano and played his heart out. “Music is a way of communicating and connection,” he said at the time. No matter what horrors he witnessed during his remarkable life, Gronowski has remained optimistic. His favourite piece of music to play during the pandemic was Louis Armstrong’s On The Sunny Side of The Street!

The portraits are on permanent display at Kazerne Dossin - Memorial, Museum and Research Centre on Holocaust and Human Rights, Goswin de Stassartstraat 153, Mechelen.

Photo: Kazerne Dossin © Jeroen Van Looy