- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Medieval manuscripts go on public view at Brussels' new KBR Museum

A new museum opening in Brussels this May will open up a hidden treasure to the public: an extraordinary 600-year-old collection of manuscripts.

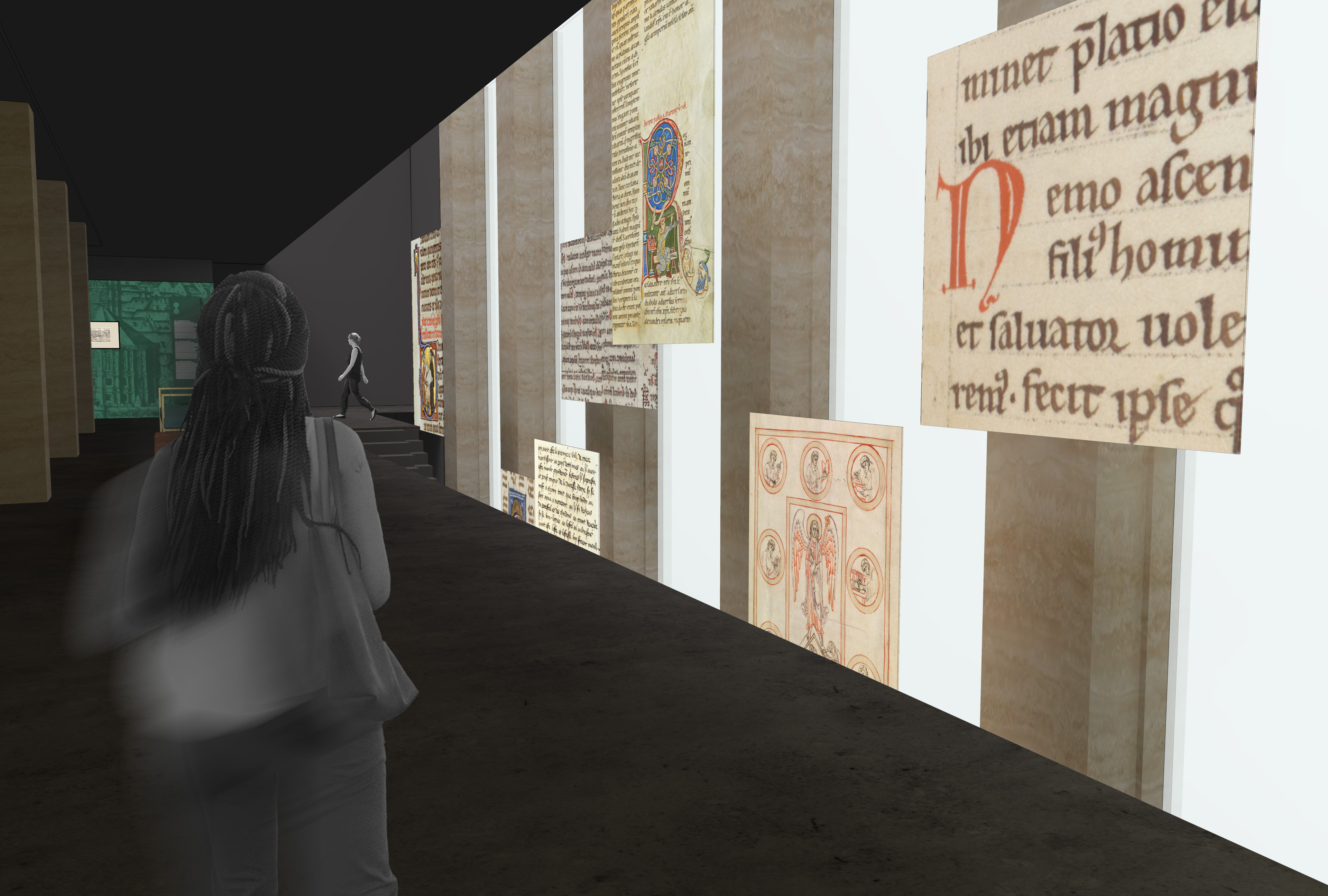

The Royal Library of Belgium is now called KBR - and the new name indicates a broadening of its mission. It will remain an essential place of research with its eight million documents but will also provide a complete cultural programme which will be centred around the new KBR Museum opening on 18 September.

The museum will offer the opportunity to discover more about Europe's medieval cultural past. It will also provide spaces for professional meetings and leisure activities. For instance, the fifth floor employee cafeteria with its stunning view of Brussels and immense terrace will no longer be a secret gem known to few, but will become a full-fledged restaurant.

A piece of history

The origins of the library lie in the collection of the Dukes of Burgundy. They were rich and powerful and wanted everyone to know it, so they invested heavily in art of all kinds. These open purses attracted a great number of the highest calibre artists to Brussels. The dukes spared no expenses when it came to showing off. For the visit of a powerful rival, Philippe le Bon commissioned more than a thousand banners, intricately painted by the greatest painters, with which to festoon the city.

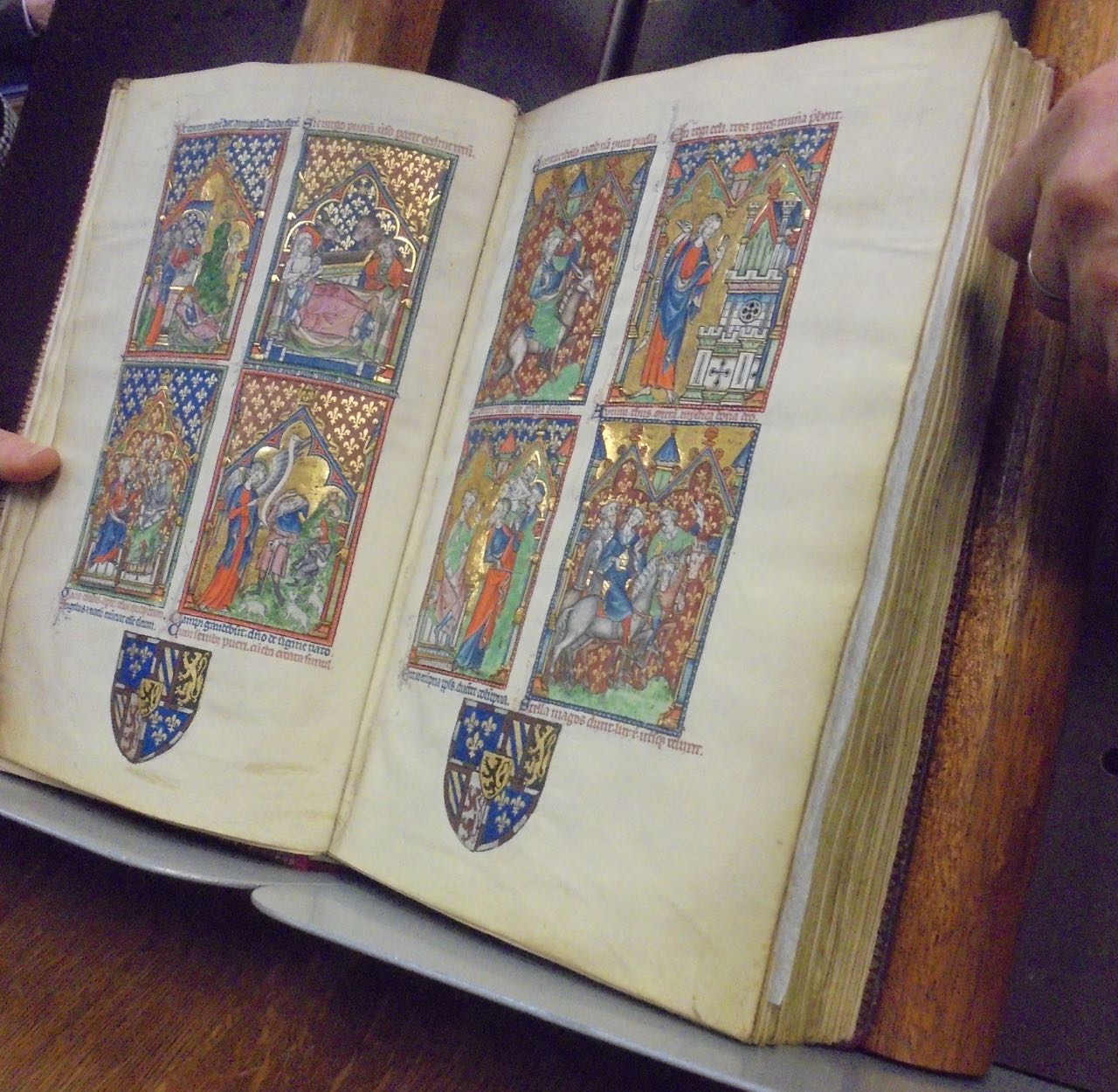

In the course of this spending spree, they amassed an extraordinary collection of 900 manuscripts. These books covered all the subjects of the time - literature, ancient history, science, morality, religion, philosophy, law, poetry and even novels - and they were beautifully illuminated with miniature paintings.

The oldest works are from the 13th century but range through to the late 15th century. Some were purchased, but many of the works were transcribed specifically for the dukes in the 15th century and their library rivalled that of the Medici in Florence, the library of the Pope at the Vatican and that of the King of France in Paris.

The Dukes of Burgundy were succeeded by the Spanish and then the Austrians, and rulers such as the Emperor Charles V added to the library, but the vicissitudes of history whittled away at the collection. When the Coudenberg Palace burned in 1731, the collection came through almost unscathed as the only two parts of the palace not to burn were the stables and the library.

However, 15 years later, the French army took the whole collection to Paris. The French were forced to return everything in 1770. Then in 1795, the French revolutionaries once again took the collection to Paris - there are contemporary descriptions of carts being drawn up to the library walls and the manuscripts being tossed out the windows into the carts for their trip to Paris.

In 1815 the collection was returned, but not everything made it back. It now stands at close to 300 manuscripts, among which are some of the most highly prized in the world such as the Chronicles of Hainaut, the Petersborough Psalter or the Stories of Charles Martel.

A delicate challenge

These extraordinary books will be on display in the new museum on rotation, because they are extremely fragile: they are sensitive to light and being kept open at the same page is very detrimental to their spines so they will only be on display for four months at a time and then must be put away for four years before they can be shown again.

"It's a real challenge because it's a permanent museum about manuscripts - but they can't be permanently on display," says co-curator Elena Savini. "That means we can adapt what we want to tell. We can change this story regularly, so every four months we can show something new or we can choose another volume of the same artist or the same writer or we can decide to display something completely different to illustrate another aspect of the art or the history of the time.

"I think it will be interesting to adapt it to the times - so it will always be new for the public who can come back and see what's changed. It's unbelievable that 300 manuscripts are still all together in the same place where they were collected for the first time, this is extremely rare."

The entire collection is being digitised in time for the opening and will be free to access online. "It can be frustrating at times that you are only seeing one page of the whole book," adds Savini. "But with this, thanks to technology, people will be able to browse the manuscript and see other pictures, other pages, also zoom into tiny details, to see some letters or some weird monster that is hidden in the corners."

The new museum will have a section on the creation of a manuscript which provides unexpected facts. For example: parchment, of which most of the pages of these books are made, was made from the hides of calves, sheep or goats and it took almost a herd per book. The 15th century, which was the apogee of manuscript production, was also its end, with the introduction of the printing press.

KBR Museum, opening 18 September, Mont des Arts 28, Brussels