- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

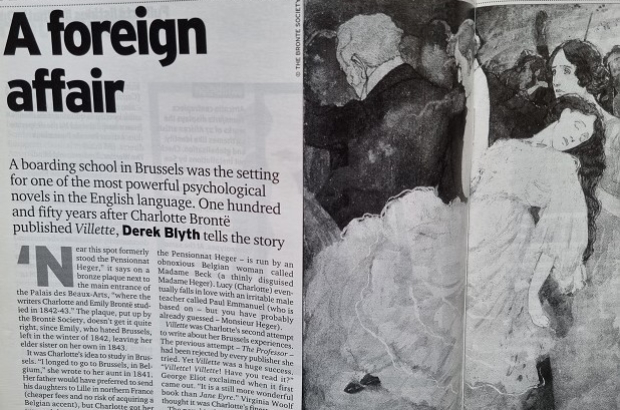

From the archive (2003): A foreign affair

“Near this spot formerly stood the Pensionnat Heger,” it says on a bronze plaque next to the Palais des Beaux-Arts, “where the writers Charlotte and Emily Brontë studied in 1842-43.” The plaque, put up by the Brontë Society, doesn’t get it quite right, since Emily, who hated Brussels, left in the winter of 1842, leaving her elder sister on her own in 1843.

It was Charlotte’s idea to study in Brussels. “I longed to go to Brussels, in Belgium,” she wrote to her aunt in 1841. Her father would have preferred to send his daughters to Lille in northern France (cheaper fees and no risk of acquiring a Belgian accent), but Charlotte got her way and the two young women arrived in the Belgian capital on a cold afternoon in February 1842, aged 24 and 26.

The plan was to spend six months studying French and good manners at the Pensionnat Heger, a smart girls’ boarding school near Place Royale. With that newly-acquired polish, the sisters planned to return to England and open a girls’ boarding school. But something happened in Brussels that changed Charlotte’s life for ever.

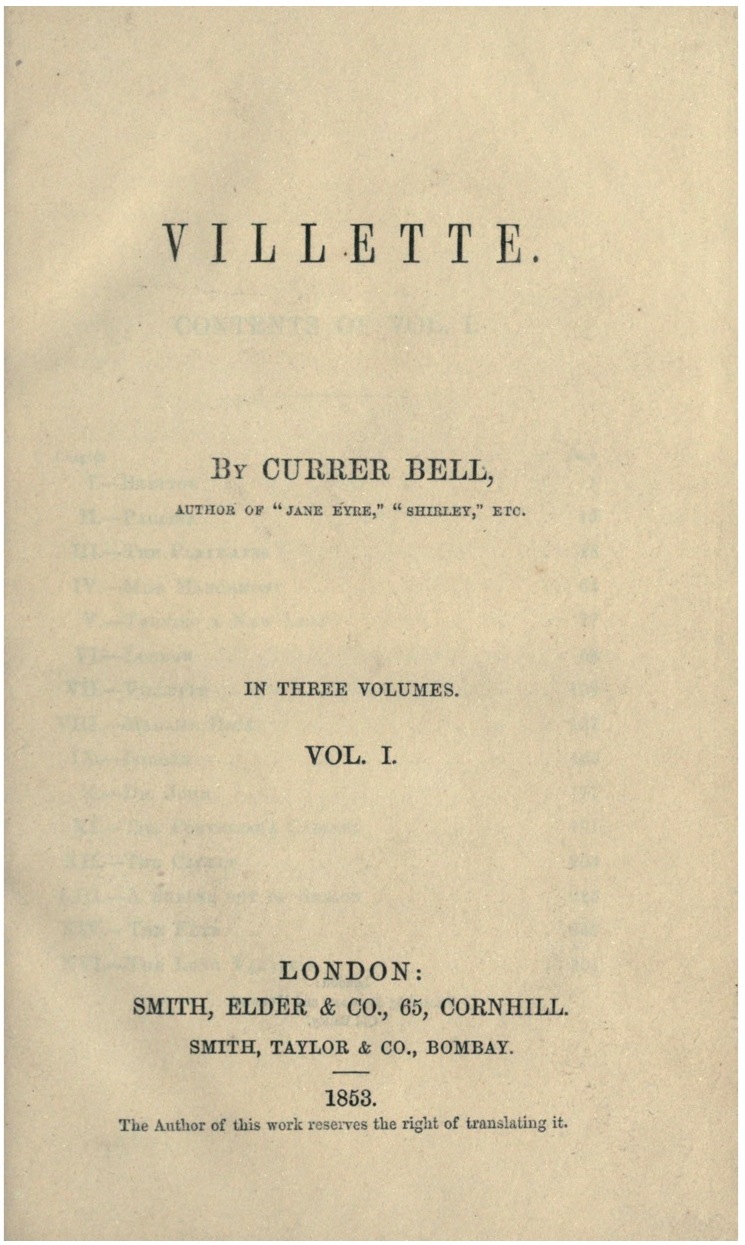

The clues emerged in Villette, her last novel, published 10 years after she had left Brussels during the winter of 1843. The plot involves a young English woman, Lucy Snowe, who travels to the city of Villette to teach in a boarding school. The school – clearly modelled on the Pensionnat Heger – is run by an obnoxious Belgian woman called Madame Beck (a thinly disguised Madame Heger). Lucy (Charlotte) eventually falls in love with an irritable male teacher called Paul Emmanuel (who is based on – but you have probably already guessed – Monsieur Heger).

Villette was Charlotte’s second attempt to write about her Brussels experiences. The previous attempt – The Professor – had been rejected by every publisher she tried. Yet Villette was a huge success. “Villette! Villette! Have you read it?” George Eliot exclaimed when it first came out. “It is a still more wonderful book than Jane Eyre.” Virginia Woolf thought it was Charlotte’s finest novel.

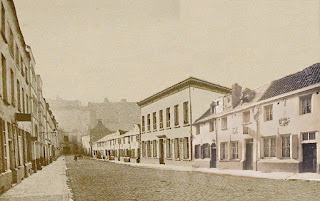

The novel included detailed descriptions of the city’s buildings and streets, prompting some of her more energetic Victorian readers to travel to Brussels and track down the sites. Eager pilgrims – many from as far off as the United States – would turn up unannounced at 32 Rue Isabelle and demand to be shown around the Pensionnat. Madame Heger (unhappy at Charlotte’s portrait of her) would give them a frosty glare, but her husband was pleased to act out the role that Charlotte had given him. “Oui, je suis Monsieur Paul,” he told one visitor.

Yet it was only in 1913 that the true depths of Charlotte’s infatuation were revealed. A small package of letters was sent to the British Museum by the Hegers’ youngest son, Paul, by that time a distinguished professor at the Free University of Brussels. The letters had been sent by Charlotte to Monsieur Heger, torn up and thrown in a bin, then carefully stitched together with a needle and thread, probably by Madame Heger.

As she read the carefully-repaired letters, Madame Heger realised that the strange English woman was infatuated with her husband. “Tell me about your children, tell me about the school, tell me… anything you like, but tell me something,” Charlotte pleaded.

Heger’s refusal to reply to the letters made Charlotte even more demented. “Monsieur, the poor do not need much to keep them alive; they ask only for the crumbs that fall from the rich man’s table, but if these crumbs are refused to them, then they die of hunger.” It did no good. Monsieur Heger never wrote back and Charlotte finally stopped writing in the winter of 1845.

Villette was her revenge. She used the novel to express her rage with Monsieur Heger, with spoilt Belgian schoolgirls, with Catholic priests, with Flemish servants, with everything Belgian. Yet there are also affectionate moments – a description of an exhibition of paintings, a festival in the park opposite the royal palace, a concert in the presence of the King – that suggest Charlotte was in fact quite fond of Belgium.

The demolition of the Pensionnat Heger in about 1911 robbed Brussels of its main Villette landmark (photomontage of how street would looked above). When the Brontë scholar Marion Spielmann travelled here in 1913, all he found was a pile of rubble. Now there is nothing left at all, except for a plaque that is too high on the wall to be seen. Brontë fans would be thrilled, I’m sure, if there was something more to show of the place – one small photograph in the lobby of the Palais des Beaux-Arts would do, just to remind readers that they are standing on the site of the romantic garden where Charlotte wandered at night listening to the church bells.

Yet even without the bricks and mortar of the Pensionnat, there are still several physical reminders of Villette in the city, such as the Cathedral, where Lucy Snowe confessed to a Catholic priest, and the Parc de Bruxelles, where she wandered in a daze after taking opium. The church on Place Royale and the little Protestant chapel next to the Fine Arts Museum also feature in Villette, as does a dingy flight of stone steps next to the Hôtel Ravenstein.

I once tried, out of curiosity, to track down the grave of Martha Taylor, a friend of Charlotte’s who died in Brussels in 1842. She was buried in the Protestant cemetery, near the Chaussée de Louvain, inspiring a tender scene in Charlotte’s other Brussels novel, The Professor. The cemetery was closed in the 19th century, but some of the gravestones were moved to the vast Brussels commune cemetery in Evere. I took bus 66 to the terminus one rainy afternoon and eventually found a broken tomb in memory of “Harriet Mary Anne, the beloved and gifted child of the Reverend Reginald Smith.” Harriet died in 1857, before the Brussels cemetery opened, which means the grave must have come from the Protestant cemetery. But there was no sign of Martha’s grave. On the way out, I asked in the cemetery office if they had any records of an English girl called Martha Taylor. The official pulled down the oldest ledger, and blew off the dust and coughed, and shook his head. The records started in 1892.

I had more luck looking for the Hegers’ tomb. Monsieur and Madame are buried in the lovely little cemetery in Watermael-Boitsfort, just on the edge of the forest. The tomb is a large grey limestone slab near the cemetery entrance. There is no mention of the part the Hegers played in one of the greatest English novels, but Madame Heger, at least, would no doubt prefer it that way.

This article was first published in June 2003

Find more information about Charlotte and Emily’s time in Belgium at the The Brussels Brontë Group. It organises talks, guided walks and other events.

Photos: Plaque, Villette cover and photomontage of street, courtesy of The Brussels Brontë Group