- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Simone Guillissen-Hoa: New exhibition showcases pioneering female Belgian architect

After tackling major societal topics such as energy and decolonisation, CIVA’s new show Simone Guillissen-Hoa explores gender in architecture while being the first exhibition ever to be devoted to the life and work of the pioneering 20th-century Belgian architect.

It honours the Chinese-born Belgian architect (1916-1996) who left an indelible legacy on Belgium’s architectural scene, yet never became a household name.

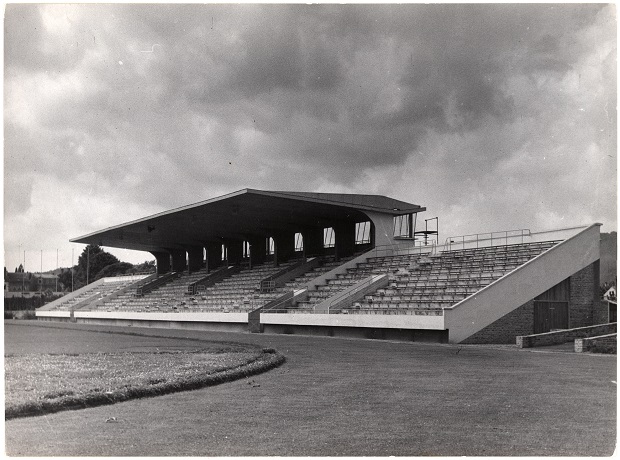

But Uccle residents may well live near one of her striking designs, most Namur residents recognise her striking sports centre in Jambes (pictured) and a statue of the architect graces the capital.

“Her work is not famous, which is why we are doing this exhibition to raise awareness,” curator Nikolaus Hirsch tells the Bulletin. Moreover, Guillissen-Hoa had an eventful and inspiring life, which is laid out in original photographs, letters, drawings and an illuminating portrait by Belgian artist Léon Spilliaert. In addition to her architectural career, the show highlights her battles as a rare woman in her field.

Born to a Chinese father and Jewish Polish mother, she was a strong and independent woman. At 25, she announced before her 1941 divorce from engineer and militant communist Jean-Guillissen: “I refuse to start my life again with a man I have stopped loving, having made my life elsewhere.” She later became a single mother. When deciding in 1950 to raise her son on her own, she pointed out that his father, editor of communist daily Le Drapeau Rouge Pierre Joye, had no intention of starting a family.

As an active member of the Belgian Resistance, she spent time in Germany’s Ravensbrück and Dachau concentration camps. During these “22 nightmare months”, her spirit was not diminished. In the early 50s, she joined women’s rights organisation the Soroptimist Association, and In the 70s, she was involved in creating the International Union of Women Architects’ Belgian section.

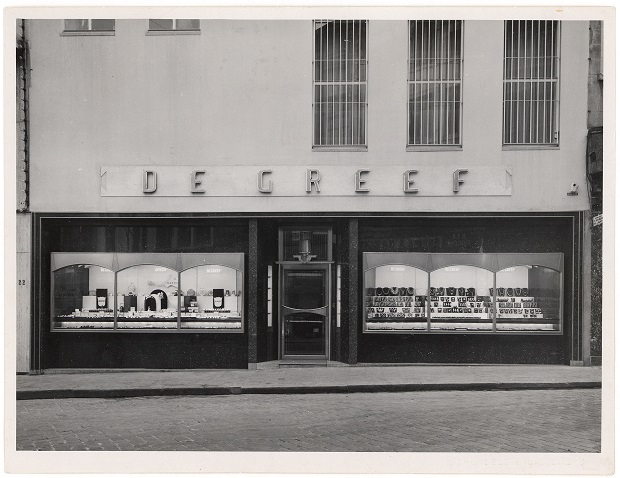

Despite a string of fascinating buildings to her name, from modernist apartments oozing intricate detail and colour and the luxurious Maison De Greef jewellery boutique (pictured) to social project homes for war victims in Deurne and a centre for the blind in Ghlin, Guillissen-Hoa failed to gain the same recognition as her male counterparts.

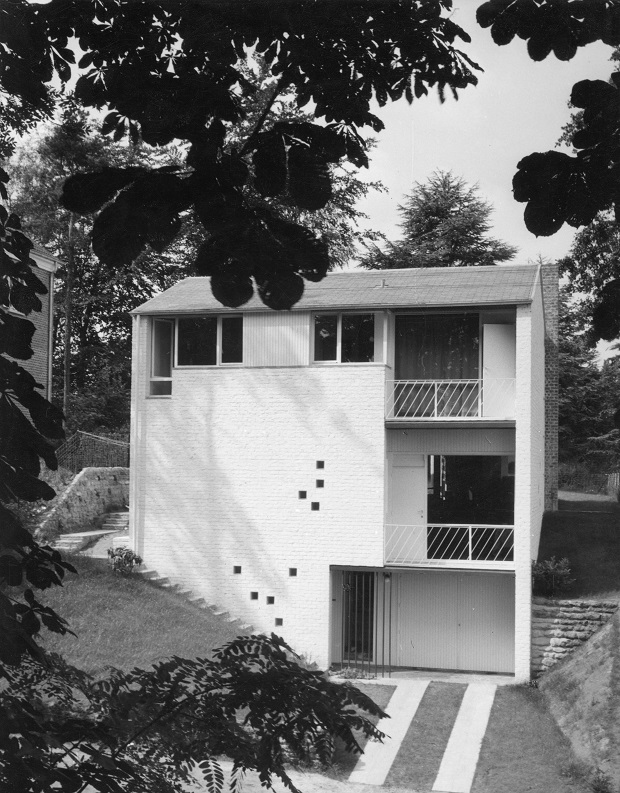

Between 1952 and 1956 she collaborated with Jacques Dupuis on projects such as Uccle’s stunning Maison Steenhout (pictured), but he was the one chosen to work on Brussels’ globally-successful 1958 World Fair.

“Simone Guillissen-Hoa is a striking example of how female architecture has been largely ignored by museums, academia and the public,” Hirsch notes. “The exhibition also marks the donation of her archive – one of the first women architects to enter our collection.”

Guillissen-Hoa, in line with other rediscovered post-war female architects such as Jane Drew (UK) and Denise Scott Brown (US), boasts many accolades to her name. She was one of the first women to gain an architecture diploma, at Brussels’ La Cambre and the first in Belgium to establish her own architecture firm, build her own house (21 Rue Langeveld, Uccle) and receive public commissions, including the Jambes sports centre, a delightful pre-school in Frameries and student housing in Louvain-la-Neuve.

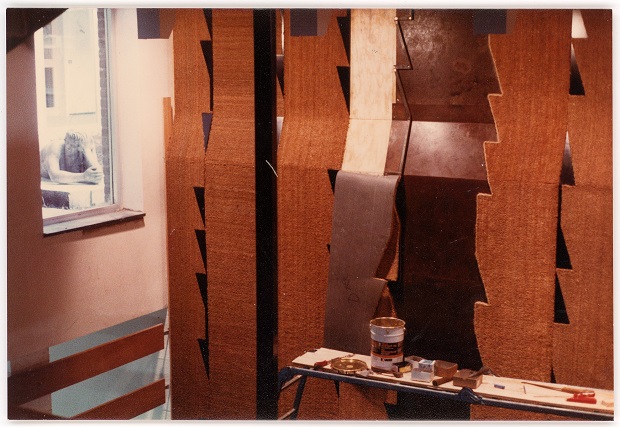

Hirsch singled out a major public commission, Tournai’s Maison de la Culture (pictured), as his favourite building. Inaugurated in 1982, it was also to be her last, and followed a collaboration with the French Ministry of Culture to study the development of cultural institutions in Belgium.

“The project proves her societal and cultural ambitions,” Hirsch says. “It also shows beautiful detail such as her collaboration with the famous textile artist Tapta in the main staircase.”

Architecture expert and exhibition tour guide Cécile Dubois’s preference is for the 1960 Villa Regniers or ‘La Quinta’ (pictured) at Baisy-Thy, near Court-Saint-Etienne in Walloon Brabant. The villa with window glass walls and an enchanting garden, also known as the ‘American house’ won joint first prize at the 1963 prestigious Van de Ven design competition.

“It has a beautiful horizontality and transparency,” Dubois says. “It’s also in keeping with a particular era: visibly wealthy people wanting to live outside the city, but not too far away.

“It is a villa that could accommodate staff. At the time, it was in the middle of nature and very isolated. The living rooms face the garden and swimming pool.”

Dubois notes that Guillissen-Hoa was “modernist but not excessively so” and her “clients were visibly pleased to live in her houses”, which were certainly different and arguably more engaging in comparison to modernist master Le Corbusier’s famous ‘machines for living’.

The exhibition’s centrepiece is a newly commissioned film, Simone (2024) by artists Eva Giolo and Aglaia Konrad. It showcases Guillissen-Hoa’s house designs and reveals their occupants enjoying daily life such as cooking, reading and playing.

Her son Jean-Pierre still lives at Rue Langeveld – the apartment and office that has awaited classification since April 2023. At the exhibition opening, his face lit up when he heard that the regional government was likely to finally approve the application.

The exhibition comes complete with a programme of talks, walks, workshops and holiday activities for children. A special educational brochure features a trail of her Uccle houses.

Simone Guillissen-Hoa

Until 22 September

CIVA

Rue de l’Ermitage 55

Ixelles

Photos: ©Simone Guillissen-Hoa/CIVA