- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

The witching hour: Two exhibitions reveal historical persecution of ‘dangerous’ women

“The history of witchcraft is marked by the sex difference of both the accused and the accusers.” This wonderfully succinct way to describe the phenomenon of the witch introduces us to the second section of a new exhibition that coincides nicely with Halloween.

While 500 years ago, the word ‘witch’ was an accusation levied against someone – nine out of 10 times a woman – today, it is worn like a badge by feminists, herbalists, ecologists and many women who simply insist on being in control of their own destinies.

Two exhibitions opened this week in Brussels that plunge visitors into the history of women dubbed witches. Within walking distance of each other, ULB’s show Witches is staged in the Vanderborght building, while KBR library’s museum hosts Witches: Avant la lettre.

As the title suggests, KBR tells us what kinds of activities women were involved in that would later be forbidden, or at least dangerous if you did not want to be accused of dabbling in the dark arts. Using miniatures from the Burgundian manuscript collection, the museum presents both fantastical (mermaids, nymphs) and realistic (cooking, nursing) illustrations of women to present a full picture of how they were perceived by men prior to the 16th century.

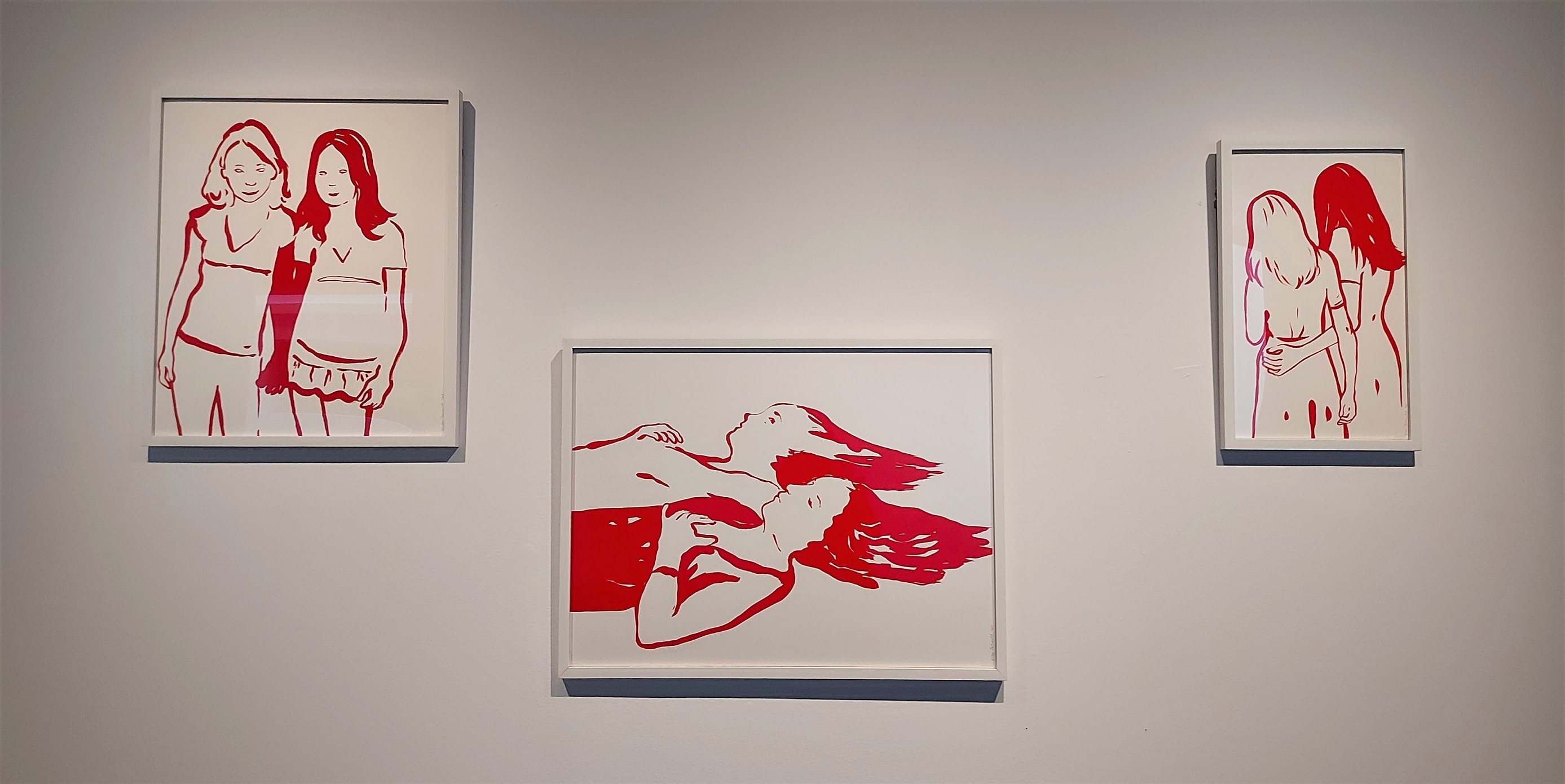

Francoise Pétrovitch’s silkscreens celebrate intimacy between girls

Francoise Pétrovitch’s silkscreens celebrate intimacy between girls

A crucial skill that would come to be seen as a threatening power was healing the sick through the use of herbs and other plants gathered in forests and fields. “When universities began to flourish in Europe, they saw the need to eliminate the competition,” says Alexia Liévin, an exhibition co-ordinator at ULB, which organised the Witches exhibition in the Vanderborght.

“Men wanted to claim medical knowledge for themselves,” Liévin continues. “And the quickest way to do that was to get rid of all the women who were skilled in the practice because they had learned it from their mothers and grandmothers before them.”

Generally speaking, women eventually abandoned the study of identifying plants with the properties needed to quell a cough or to ease gout, let alone making pastes or syrups from them. “They had had skills in this area, but they lost them because they were – quite literally – burned.” Modern witchcraft, she says, “is all about getting all of this back.”

Medea is resigned to her fate in one of the exhibition’s highlights ©Joseph Stallaert, Médée, 1880, Huile sur toile, 158 x 235 cm, Collection artistique de la commune de Schaerbeek

Medea is resigned to her fate in one of the exhibition’s highlights ©Joseph Stallaert, Médée, 1880, Huile sur toile, 158 x 235 cm, Collection artistique de la commune de Schaerbeek

But she’s not referring just to the ability to distinguish St John’s wort from tickseed. The exhibition Witches starts off with a look at the 1960s, when women took the streets in pointy black hats and capes to insist on autonomy over their own bodies and, by extension, their own lives.

“It’s really about being free, being independent, being daring,” says Liévin. “And being ourselves in a capitalistic world that is destroying the earth.”

Witches is set up thematically, with this ‘new witch’ starting things off, a history of the witch following, then back to contemporary works at the end. This works only partially as the entire first chapter feels like a capsulised history of 1960s feminism to today with tenuous links to 16th-century persecution.

Bright red-on-white silkscreens by contemporary French artist Francoise Pétrovitch of girls and body parts, for instance, are striking but seem lost in a story we have not yet been told. While it could have been powerful to be immediately confronted with an image of a witch in the street, and perhaps the popular slogan “We are the granddaughters of the witches you couldn’t burn,” it would have needed to transition quickly to the historical section in order to maintain a momentum.

A Belgian rendition of the Witches Sabbath ©David Teniers II, Scène de Sabbat, 2e moitié du XVIIe, Huilde sur toile, Musée de Poitiers

A Belgian rendition of the Witches Sabbath ©David Teniers II, Scène de Sabbat, 2e moitié du XVIIe, Huilde sur toile, Musée de Poitiers

So visitors might want to consider diving right into part two, then ending with part one. Each of the four sections comes with a lengthy text – in English, French and Dutch – to set the scene ahead. This is extremely helpful in understanding some of the art and artefacts in Witches, as individual pieces are not contextualised.

There is some great stuff here, both contemporary and historical. A painting by 19th-century Belgian artist Joseph Stallaert pictures Medea, dagger in hand, gazing at her small children, her face a mixture of dread and sorrow.

Granddaughter of the son god Helios, Medea was in possession of magical powers. In some versions of her story, she murders the children she shared with Jason when he abandoned and banished them all. While it’s impossible to say for sure, the story of Medea could have been the root of the eventual popular myth that witches kidnapped and ate babies – or delivered them to the devil so he could eat them himself. Turn around to see a black-and-white film from the 1920s that visualises this quite nicely.

Another gem in Witches is 17th-century Belgian painter David Teniers II’s rendering of a Witches’ Sabbath. These paintings were popular in his time for depicting all of the nasty things witches would get up to together in the woods, in caves or anywhere else others feared to tread. Teniers’ witches are inside a rustic home, in the presence of all manner of odd creatures, with one witch naked, a broom between her legs.

In the end, many of the works here are worth seeing, but the exhibition is less than the sum of its parts. Ironically, there is a whole lot of text but not enough contextualisation. Signing up for a tour is probably the best way to get the most out of Witches.

Witches, Until 16 January, Vanderborght building, Rue de l’Ecuyer 50. Many fringe events includes performances, workshops and conferences.

Photo top ©Thomas Samson/AFP/BELGA. Sorry! Our prize giveaway has now closed and the winner has been notified.