- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

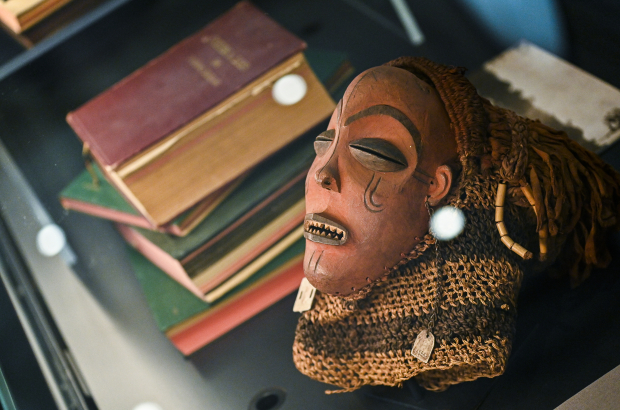

Africa Museum begins large-scale investigation into looted artefacts

The Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren has requested help in its investigation into whether or not objects from its collection have been unlawfully acquired

The Belgian government has agreed to return looted art from the colonial period to the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), but with tens of thousands of artefacts to assess, the origin of many is difficult to trace.

Many pieces from the collection of the Africa Museum in Tervuren were obtained by theft, violence or as spoils of war during the period between 1885 and 1960. The legal ownership of all these unlawfully obtained documents will be transferred to the DRC.

"The time has come for the return of the objects that have been unlawfully removed from Congo, because they belong to the Congolese people," state secretary for science policy Thomas Dermine said at a press conference at the Africa Museum this week.

The decision is in response to a request for the return of the artefacts from the DRC’s President Félix Tshisekedi, a request first made by the country’s first independent president Joseph Kasa-Vubu in 1960.

The museum has revealed that at least 885 pieces in its collection were definitely acquired illegally; that is just 1% of the total collection housed in Tervuren.

One of those pieces is the nkisi of King Ne Kuko, a showpiece of the Africa Museum. A nkisi is a container that is believed to hold an ancestral spirit. In this case it is a statue which documents show was clearly looted from a village near the port city of Boma in 1878.

The statue came into the hands of Belgian Alexandre Delcommune, a rubber and ivory trader who had clashed with some of the local kings. To punish them, he ordered mercenaries to attack their villages. The nkisi was looted from the village of King Ne Kuko.

The agreement to return those artefacts removed through illegal activity does not mean they will disappear from the Africa Museum immediately. Thomas Dermine says a distinction must be made between the legal ownership of the artefacts and the physical return itself. The DRC will therefore again take ownership of these looted pieces, but the physical transfer of them will take some time.

"We now need to build a relationship with the Congolese authority to make sure that those objects can return to Congo under good conditions," Dermine said. In practice, there will be a 'refund deposit' agreement: the artefacts will remain in Belgium until the DRC requests one back. This gradual return should ensure the proper preservation of the artefacts.

In the meantime, Dermine wants to put together a scientific committee in cooperation with the DRC authorities to investigate how the various pieces ended up in the collection of the Africa Museum.

Many of the thousands of pieces on show have been acquired legally, through donations or sales, such as the ‘prauw’ or canoe that ended up in Belgium in 1957. "This was a gift from the Congolese people following King Leopold III's visit," says Guido Gryseels, the director-general of the museum. “But the question remains as to what extent did the governor or the regional manager at the time instruct or pressure the population into making that prauw."

Of 50,000 pieces, or 58% of the collection, the museum is certain that they were lawfully obtained. The origin of the remaining 42% is more difficult to determine. This will take time, money and human resources.

The investigation in cooperation with partners in the DRC will therefore need help. “I expect that we will need at least eight extra people, just for research over the next five years, and that will be just for the important collections," said Guido Gryseels.