- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Heart of glass: MusVerre in northern France explores the human body in year-long exhibition

Coloured glass spikes embellish the red-brick homes surrounding MusVerre, a first inkling of how the village of Sars-Poteries still cherishes its once flourishing glassware industry.

These decorative waterproofing objects (pictured below) glint away within the pastoral landscape of the Avesnois Regional Park, close to the Belgian border. They are a testament to the local population’s pride in the once thriving factories that fuelled the economy in the region.

France’s first museum space devoted to glass is an important cultural landmark. The low-lying contemporary building clad in local blue stone features striking chiselled edges that echo crystalline silica, the original material of glass. Opened in 2016, the extensive site encompasses spacious exhibition areas, an adjacent studio for artist residencies and a workshop dedicated to preserving the ancient and intricate techniques of blowing glass.

The mission of MusVerre also includes promoting the craft of glass on an international stage and reinforcing the museum’s role in contemporary creation. Hence the staging of temporary exhibitions, including À corps, which runs from 21 February until 4 January.

Showing some 28 works by 25 artists from France and around the world, it is a breathtakingly beautiful and poetical exploration of numerous facets of the human condition.

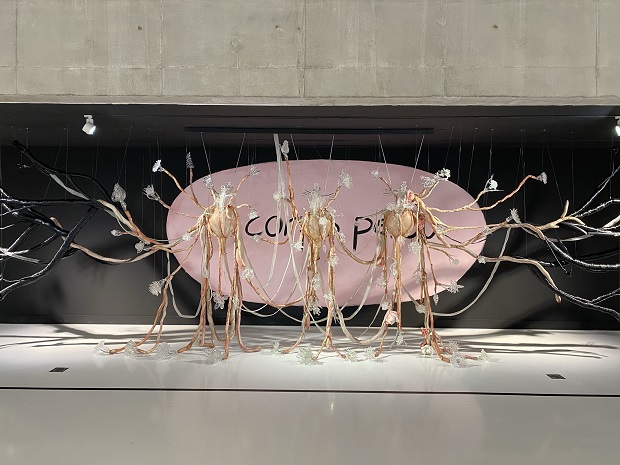

It begins in the minimalist white space of the foyer with the striking in-situ work Flowering out into the world (powering out into the world) by Simone Fezer (pictured main image and above). The German artist has created three human hearts out of blow glass, interconnected by a network of sinuous tubes adorned with delicate glass flowers. Suspended from the ceiling, the installation invites a reflection on the human capacity and need for connection.

The second work is a pair of stained glass windows Days of the Week by Belgian artist Wim Delvoye, renowned for his Cloaca series of art installations that recreate the human digestive process. This bodily function is reproduced here in fragile works that blend medieval motifs with juxtaposed images of an intestine and an x-ray.

The exhibition is then divided into two sections; the first is a darkened space, which reinforces the notion of introspection. Among the invitations to marvel at the complexity of the human body is an installation by Manon Fontaine’s that recreates the circulation of blood. Again, it underlines the importance of human connection. Another eye-catching work is a suspended blown glass skeleton by Philippe Beaufils that hovers mid-air, questioning the role and physical place of man in the world. Belgian artist Willy Declercq cast both his and wife’s buttocks to show the body in a state of harmony, linked by a pair of hands (pictured).

In the second light-filled space, the beauty of the body is celebrated. Hungarian artist Mari Meszaros approaches the theme with delicacy in Annonciation (pictured), while Belgian Sandra De Clercq similarly explores a female-centred universe in her wall installation of a spiral of breast-shaped forms, inspired by ethnic motifs.

Florian Lechner is one of the most important glass designers in Germany. The 82-year-old Munich native is a pioneer of a heat-formed glass technique of known as fusing that creates a transparent and liquid effect to his monumental series of figures (pictured).

The breadth of techniques applied to or employing glass is an astounding feature of the exhibition. In a clear and transparent form, glass sculpture can appear solid and light, while glazing techniques and the use of colour and other materials inject subtility and variety. The multitude of perspectives contribute to a detailed examination of the fragility and wonder of the human body, evoking intimacy and a wider reflection on the complexity of human experience and existence.

How glassworkers’ personal pieces launched the museum

MusVerre’s temporary exhibitions complement a collection of some 800 works, historic and contemporary. The centrepiece is the ‘bousillés’, or whimsies in English. These are the personal pieces created by factory glassblowers during their work breaks, dating from the early 19th century until the closure of the factories in 1937. The custom arose because learning the trade was lengthy and arduous; the more practice they acquired contributed to their training.

“These are authentic pieces in which they showed off their skill and know-how,” explains the exhibition co curator Laura Bouvard. “They usually chose to make objects that were destined as gifts for family members and were often highly symbolic.”

Tableware such as multi-hued cake stands and goblets form much of the collection, alongside objects including shisha water pipes. Shown together, these homely yet lovingly-crafted works demonstrate the vitality and creativity of the glassblowers and evoke a bygone era when these precious pieces were treasured by local families.

When the priest Louis Mériaux arrived in Sars-Poteries in 1958, he discovered residents’ profound attachment to the lost tradition of glassmaking. He also recognised the value and the heritage of the works proudly on display in their homes. Mériaux raised funds to purchase the former home of the factory owner, the Chateau Imbert. He also persuaded parishioners to lend him their ‘bousillés’ for a first exhibition staged there in 1967. Following its success and a subsequent international symposium, a permanent collection was created, which would lead to the founding of the Musée-Atelier du Verre.

The priest was also behind the drive to preserve the craft of glass making. “He wanted to relight the ovens so that all this knowledge and skill was not lost,” says Bouvard. “There is an important issue of transmission, which continues today,” she points out.

It is safeguarded thanks to the museum’s Atelier, a busy workshop equipped with cutting-edge equipment for classes and demonstrations. Artist residencies encourage rising talents to develop their glass skills, with examples of their works joining the museum’s extensive collection.

At the heart of the studio are the red-hot furnaces; their blistering heat ensuring the glass can be shaped and formed. It is a complex and mentally- and physically-demanding process. Artists demonstrating the craft underline the need for patience and concentration as they attach glass to the end of a blowpipe, insert it repeatedly into the kiln, blow intermittently into the rod and slowly mould the glowing shapes. It takes at least 10 years to master the craft that dates from ancient times.

It is mesmerising to watch as they manipulate the molten glass with the help of a multitude of specialised tools. Although modern technology has transformed production, these traditional techniques are surviving thanks to the passion of artisans who are adapting them for contemporary art and design.

The workshop is also responsible for manufacturing the spikes adorning local roofs. “The only record of their manufacture is here in Sars-Potieres and the surrounding villages,” explains Bouvard. When the new museum re-opened, the atelier started to make new spikes in more contemporary hues. They are distributed freely and there’s currently a year-long waiting list to receive one of these hand-crafted tributes to the region’s glory glass days.

MusVerre

Rue du Général de Gaulle 7

Sars-Poteries

France

Photos: (main image) Simone Fezer Flowering out into the world, photo © Gottfried Stoppel; Willy Declercq - Hamonie; Florian Lechner, Les Déesses des quatre parts de la terre ©Florian Lechner ©Laurent Sully-Jaulmes musée des arts décor