- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

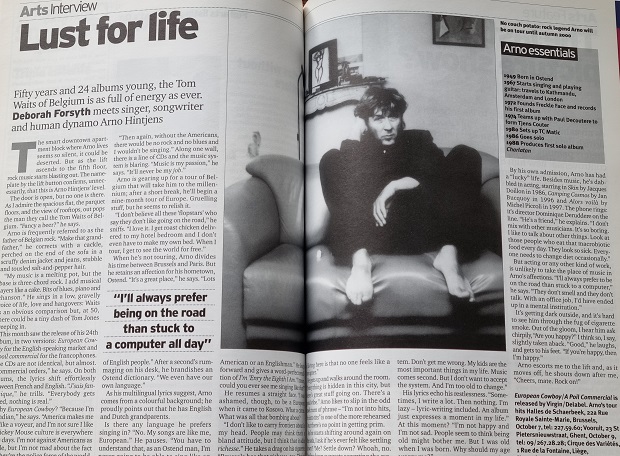

From the archives (September 1999): The Bulletin meets Arno

This article was published in The Bulletin in September 1999

The smart downtown apartment block where Arno lives seems so silent, it could be deserted. But as the lift ascends to the fifth floor, rock music starts blasting out. The nameplate by the lift button confirms, unnecessarily, that this is Arno Hintjen’s level.

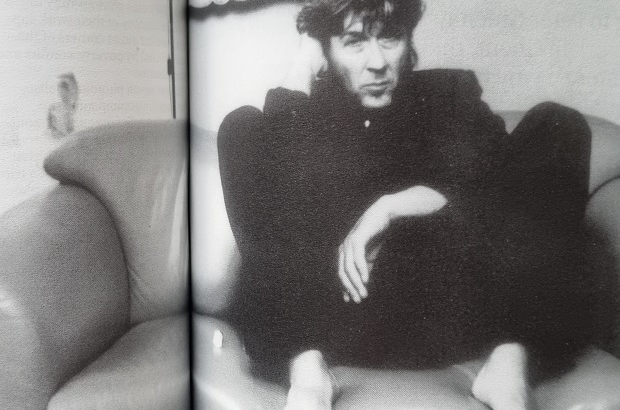

The door is open, but no one is there. As I admire the spacious flat, the parquet floors, and the view of rooftops, out pops the man they call the Tom Waits of Belgium. “Fancy a beer?” he says.

Arno is frequently referred to as the father of Belgian rock. “Make that grandfather,” he corrects with a cackle, perched on the end of the sofa in a scruffy denim jacket and jeans, stubble and tousled salt-and-pepper hair.

“My music is a melting pot, but the base is three-chord rock. I add musical layers like a cake. Bits of blues, piano and chanson.” He sings in a low gravelly voice of life, love and hangovers: Waits is an obvious comparison but, at 50, there could be a tiny dash of Tom Jones creeping in.

This month saw the release of his 24th album, in two versions: European Cowboy for the English-speaking market and A poil commercial for the francophones. The CDs are not identical, but almost. “Commercial orders,” he says. On both albums, the lyrics shift effortlessly between French and English. “J’suis fantastique,” he trills. “Everybody gets naked, nothing is real.”

Why European Cowboy? “Because I’m an Indian,” he says. “America makes me feel like a voyeur, and I’m not sure I like it. Mickey Mouse culture is everywhere these days. I’m not against Americans as people, but I’m not mad about the fact that they’re the police force of the world.

“Then again, without the Americans, there would be no rock and no blues and I wouldn’t be singing.” Along one wall, there is a line of CDs and the music system is blaring. “Music is my passion,” he says. “It’ll never be my job.”

Arno is gearing up for a tour of Belgium that will take him to the millennium; after a short break, he’ll begin a nine-month tour of Europe. Gruelling stuff, but he seems to relish it.

“I don’t believe all these ‘flopstars’ who say they don’t like going on the road,” he sniffs. “I love it. I get roast chicken delivered to my hotel bedroom and I don’t even have to make my own bed. When I tour, I get to see the world for free.”

When he’s not touring, Arno divides his time between Brussels and Paris. But he retains an affection for his hometown, Ostend. “It’s a great place,” he says. “Lots of English people.” After a second’s rummaging on his desk, he brandishes an Ostend dictionary. “We even have our own language.”

As his multilingual lyrics suggest, Arno comes from a colourful background; he proudly points out that he has English and Dutch grandparents.

Is there any language he prefers singing in? “No. My songs are like me, European.” He pauses. “You have to understand that, as an Ostend man, I’m never going to be able to sing like an American or an Englishman.” He leaps forward and gives a word-perfect rendition of I’m ‘Enry the Eighth I Am. “I mean, could you ever see me singing like that?”

He resumes a straight face. “I was ashamed, though, to be a European when it comes to Kosovo. What a circus. What was all that bombing about?

“I don’t like to carry frontiers about in my head. People may think that’s a bland attitude, but I think it adds richesse, too. The joy of living here is that no one feels like a foreigner.”

He gets up and walks around the room. “Everything is hidden in this city, but there’s great stuff going on. There’s a good vibe.” Arno likes to slip in the odd raw turn of phrase – “I’m not into hits, I’m into tits” is one of the more rehearsed – but there’s no point in getting prim.

As he starts shifting around again on the sofa, I ask if he’s ever felt like settling down? “Me? Settle down? Whoah, no. Settling down suggests accepting the system. Don’t get me wrong. My kids are the most important things in my life. Music comes second. But I don’t want to accept the system. And I’m too old to change.”

His lyrics echo his restlessness. “Sometimes, I write a lot. Then nothing. I’m lazy – lyric-writing included. An album just expresses a moment in my life.” At this moment? “I’m not happy and I’m not sad. People seem to think being old might bother me. But I was old when I was born. Why should age worry me?”

By his own admission, Arno has had a “lucky” life. Besides music, he’s dabbled in acting, starring in Skin by Jacques Doillon in 1986, Camping Cosmos by Jan Bucquoy in 1996 and Alors voilà by Michel Piccoli in 1997. The phone rings: it’s director Dominique Deruddere on the line. “He’s a friend,” he explains. “I don’t mix with other musicians. It’s so boring. I like to talk about other things. Look at those people who eat that macrobiotic food every day. They look sick. Everyone needs to change diet occasionally.”

But acting, or any other kind of work, is unlikely to take the place of music in Arno’s affections. “I’ll always prefer to be on the road than stuck to a computer,” he says. “They don’t smell and they don’t talk. With an office job, I’d have ended up in a mental institution.”

It’s getting dark inside, and it’s hard to see him through the fug of cigarette smoke. Out of the gloom, I hear him say chirpily, “Are you happy?” I think so, I say slightly taken aback. “Good,” he laughs, and gets to his feet. “If you’re happy, then I’m happy.”

Arno escorts me to the lift and, as it moves off, he shouts down after me, “Cheers mate. Rock on.”

Arno essentials

1949 Born in Ostend

1967 Starts singing and playing guitar: travels to Kathmandu, Amsterdam and London

1972 Founds Freckle Face and records his first album

1974 Teams up with Paul Decoutere to form Tjens Couter

1980 Sets up TC Matic

1986 Goes solo

1988 Produces first solo album Charlatan