- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Belgian cycling legend Yvonne Reynders honoured in elite women’s road race

She won more world race titles than Belgian cycling legend Eddy Merckx, yet Yvonne Reynders’ glittering cycling career has largely gone unnoticed.

The Brussels-born sportswoman became a world champion road cyclist for the third time in her career on 11 August 1963. But in those gender inequality days, such sublime achievements by women like Reynders, garnered little or no attention by the world’s media.

Belgium boasts a long and glorious history of cycling and helped pioneer it as a professional sport. While male stars have always been feted, the women’s competitions were another story. If they missed out on a medal, their only reward would be a brisk handshake.

Now 86, Reynders is finally being honoured beyond Belgium’s elite and amateur cycling circles. To commemorate the 60th anniversary of her remarkable 1963 victory, a specially dedicated Grote Prijs Yvonne Reynders elite race took place for the first time this week in Noorderwijk, near Antwerp.

The one-day race was won by Dutch rider Eline Van Rooijen, closely followed by Belgium’s Sanne Cant (pictured above left with Reynders), while the Netherlands’ Kirstie Van Haaften took third place.

Competitors were in unison for their praise of Reynders who became a trail-blazer, not just for women’s cycling, but for women in sport globally. Her third world title in the Flemish Ardennes, secured a hat trick of wins in this category after earlier victories in 1959 and 1961.

In the 1963 world road race, Reynders had home advantage over her great rival, the equally talented British rider Beryl Burton, who had lost out to Reynders in 1961 and still had something to prove. The two were fierce competitors and their rivalry was legendary. This time, there was no nail-biting finish as Burton was out of the race early on after a collision. Reynders contested the final sprint with 15 other riders before claiming the world title.

With success at her feet, Reynders went on to clinch another gold medal in world road cycling in 1966, beating Burton again into fifth place. Between them, Reynders and Burton dominated women’s road and track racing, winning 13 out of the 16 road and pursuit gold medals between 1959 and 1966.

But Reynders’ path to success was littered with obstacles, which makes her story even more remarkable. Born in Schaerbeek in August 1937, the young Reynders dreamed of following in the footsteps of her idol, the great Dutch sprinter Fanny Blankers-Koen, who won gold in the 1948 London Olympics.

Realising that she lacked the speed needed to win medals, she switched to the discus and enjoyed some success, claiming Belgian junior titles in 1955 and 1956. By this time, the 16-year-old had left school and taken a job delivering coal, but she needed wheels to dispatch the sacks of fuel. Her early passion for cycling was refuelled when she rode a carrier tricycle every day to complete her 16km coal round in Antwerp.

Muscle mass built up during her discus throwing days had to be shed if she were to be successful on two wheels. So after an arduous day at work, she rode her tricycle another 100-140km to shed weight. This proved invaluable when, race ready, she swapped the tricycle for two wheels.

In those days, regular training on the velodrome in Antwerp was strictly for men only. Undeterred, Reynders knew she had to compete with them if she was to stand any chance of success. She regularly outclassed the boys in training by disguising herself as a young man to gain entry to the circuit.

Delivering coal meant Reynders’ income was meagre and funding the cost of travel to races was a frustrating and ongoing challenge. There was little support from the Belgian cycling authorities for women at the time and Reynders’ parents were poor. Sleeping in friends’ cars, scraping and saving enough money to realise her dream to get to championships and surviving on cheap food, were her only options. But she eventually lifted these barriers out of her path to become one of Belgium’s greatest sporting achievers.

However, Reynders’ career was blighted in 1967 when she tested positive for the amphetamine Ephedrine. The cyclist vehemently denies to this day that she took an illegal substance. Many say that the tests were falsified as the only riders who failed the dope test were Belgian. Moreover, many deemed that it was an attempt to discredit women cycling as a whole. Friends of Reynders say she had her suspicions about the authenticity of the testing confirmed by an old cycling acquaintance years later. Reynders was suspended for three months, but the ban deeply upset her. She called it a huge injustice and promptly quit racing for 10 years in disgust. But in 1976, at the age of 39, she came out of retirement and won bronze at the road world championships in Italy before retiring for the final time, enjoying a somewhat calmer career as a pedicure specialist.

Nowadays, Reynders, who lives near Antwerp, prefers to stay out of the spotlight and regularly suffers bouts of ill health. When she feels well enough, she pops in to Café Welkom in Noorderwijk to catch up with the owner, her close friend and cycle enthusiast, Jo Helsen.

Speaking to The Bulletin, Helsen, who raises money for charities each year from his camper van during the Tour de France, said: “Yvonne was a child of her time and it wasn’t the time for women in sport unfortunately. Her childhood and life has not been easy for her but Yvonne is a wonderful, honest person with a great sense of humour. She is a strong, determined lady even today. She achieved such great things and Belgium is slowly recognising her as the great sporting hero she is.”

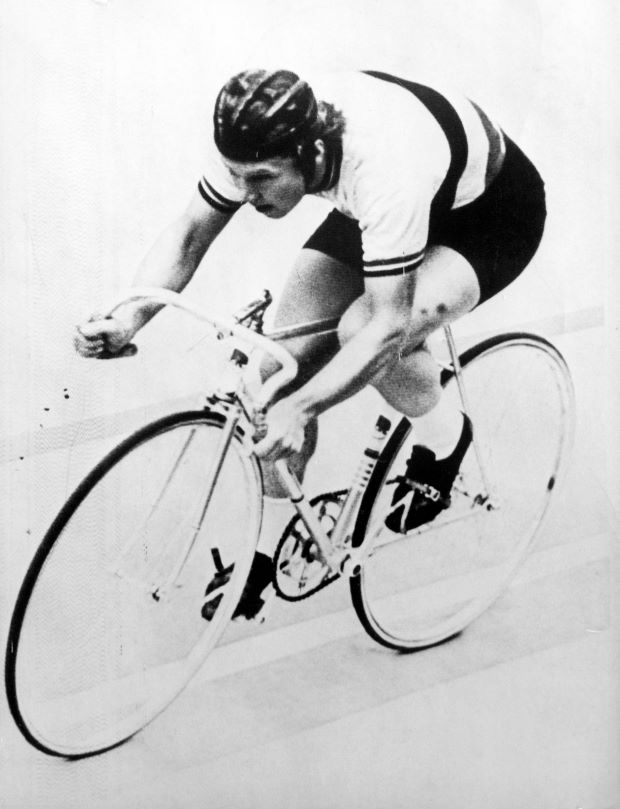

Photos: courtesy Yvonne Reynders; Yvonne Reynders at San Sebastian world championship in 1964 ©Belga Photo Archives