- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Europalia Georgia: Flagship exhibition on avant-garde artistic scene is a rich revelation

The biennial arts festival Europalia has opened with its flagship exhibition, The avant-garde in Georgia (1900-1936), a feast of vibrant and innovative art.

Showing at Bozar until 14 January, it reveals a largely forgotten chapter in the history of art: an extremely fertile period for a group of talented, adaptable and visionary artists who fused Eastern and Western art influences.

Their body of work remained under the radar for decades, victim of the particularly turbulent history of this southern Caucasian country. Located at the crossroads of Eastern and Western civilizations, Georgia has suffered from Soviet occupation and persecution.

Today, as it continues its unshackling from Russian influence, the country aspires to join the EU. Hence its enthusiasm for participating in the prestigious biennial; the first time that such a wide-ranging exhibition on the avant-garde has been presented outside of Georgia.

More than 150 works attest to its singularly rich artistic heritage. The show starts at the beginning of the 20th century when the Georgian capital Tbilisi was a cosmopolitan ‘place to be’. The symbolist movement was the major artistic expression and highly influential in paving the way for the country’s avant-garde.

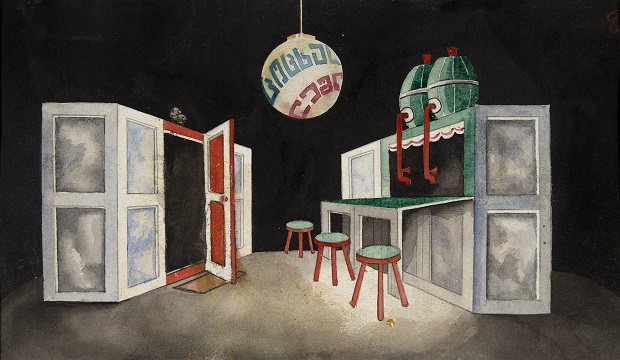

From 1918, when Georgia declared independence until the Soviet invasion in 1921, artists and poets enjoyed a brief golden age. Cafes and bars in the capital were the backdrop for this flourishing scene, gathering all the main creatives and thinkers of the age. Testifying to this artistic fervour were the colourful murals that embellish their walls.

Painter and photographer Gigo Gabashvili studied in St Petersburg and Munich, two cities that influenced many artists in Tbilisi. If he was reputed as a realist, it was only in the post-Soviet period that he was finally recognised as a key Georgian symbolist who was far-sighted in his exploration of androgynous figures. Mysticism was another theme, a reflection of Eastern spirituality that was ever-present in the country despite its conversion to Christianity in the 4th century.

From an evocative painting of falling angels to a sculpturally expressive photograph of a woman with wings (pictured), Gabashvili was highly experimental and diverse in his technique and subject matter.

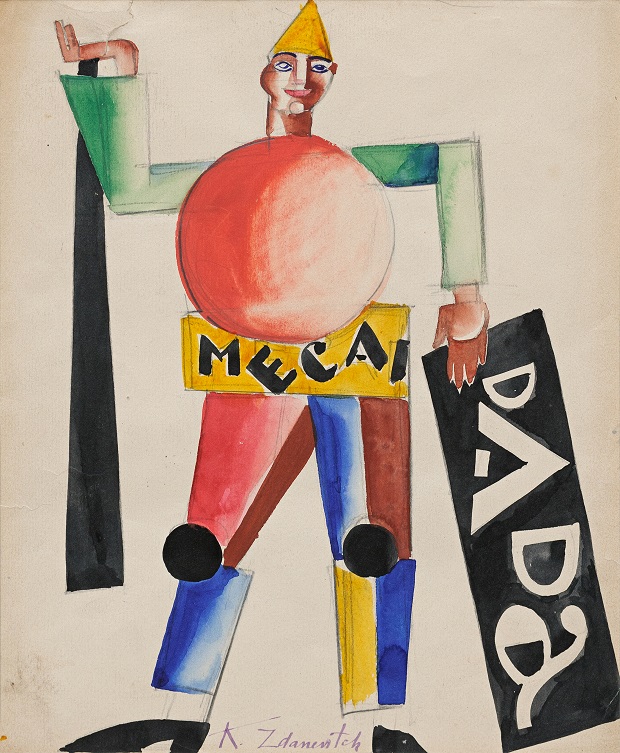

The 41° group was a prime example of collective influence, centered around futurism and a predilection for excess. Named after the geographical latitude of not only Tbilisi, but other cities, such as New York and Madrid, the alcoholic degree of vodka and the temperature at which the human body loses conscious.

Brothers Kirile and Ilia Zdanevich were key members of the literary and artist group. The former was a stage designer as well as an artist, who experimented with book design and typography. In his sketch for the play Maelstrom (pictured), his minimalist graphic skills create striking images.

Both brothers were influential in promoting the work of self-taught sign painter Niko Pirosmanishvili (Pirosmani), who encapsulated the Georgian avant garde. His large-scale primitive works were painted with a black backdrop on a variety of materials, including cardboard, tin and oil cloth.

They bear the hallmarks of their original promotional purpose with dramatic scenes played out and intriguing symbolist series of objects, as evident in The Feast of Four Citizens (pictured). The story of Pirosmanishvili, Georgia’s most famous painter, is equally compelling as he lived in destitution and only achieved full recognition posthumously.

The avant-garde in Georgia was characterised by the diversity and vitality of its artistic movements, from neo-symbolism, futurism and dadaism, to expressionism and everythingism. The latter, introduced by Ilia Zdanevich broke all academic codes, reflecting the influences of his periods abroad. Artist giants such as Salvador Dali were among the figures who recognised the Georgian’s vision and talent

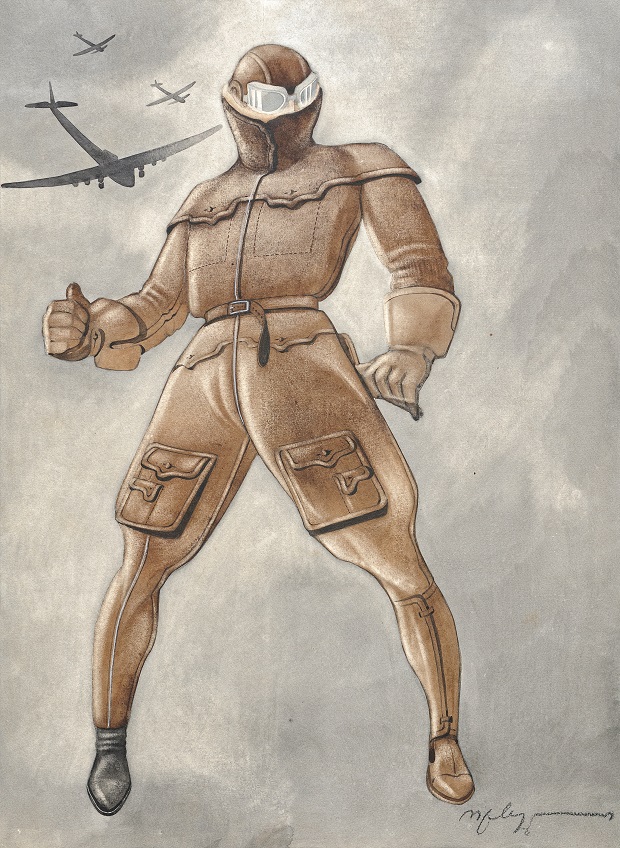

Another particularity was artists’ interest in their heritage, from choral polyphony to archaeology. They were also multidisciplinary, a necessary quality as Soviet censorship following the 1924 uprising drove them to express their creativity in the lesser-controlled theatre and cinema scenes.

Among the artists who turned their talents to set and costume design was Petre Otskheli, who also played a pivotal role in this intense period (The Flying Painter, pictured above). He was an influential modernist who defied Soviet totalitarianism to portray meta-heroes, such as his sketch for the film The Winged Painter (pictured below). The universality and power of his images ultimately cost him his life; Otskheli was executed in 1937.

An excerpt of the silent film Amok serves as a teaser for a later full screening at Cinematek. The subversive 1927 feature by Kote Marjanishvili recounts how a married woman in a British colony approaches a drug-addict doctor for an abortion. When he accepts on condition that she spends the night with him, she refuses, with tragic consequences.

As a result of Stalin’s purges from 1936, many of this remarkable generation of artists were deported and assassinated. One exception was Ilya Zdanevich, who remained in Paris, where his collaborations included textile designs for fashion designer Coco Chanel.

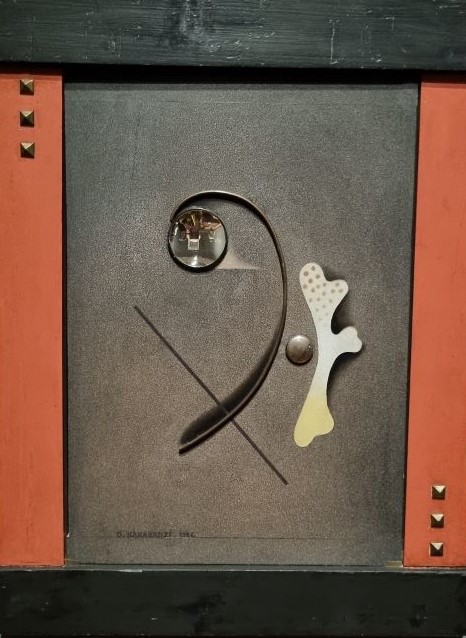

Another who survived, was the multi-talented David Kakabadze, who worked for a while within Soviet confines. Among his works on display are a 1913 self-portrait in a mirror, all angular minimalist lines and early nostalgic landscapes. Following the purges, he remained in Tbilisi and attempted to incorporate elements of social realism in his work, as shown in Demonstration in Imereti (pictured), where the Georgian landscape dominates the amorphous figures protesting.

It was the quality of an earlier and unknown abstract work by Kakabadze, Object with lenses and mirrors, 1924, (pictured) that convinced Europalia’s artistic director Dirk Vermaelen of the merit of staging the exhibition.

If the avant-garde movement remained within the collective memory of later artists, it was only after the fall of the soviet union that new research uncovered their full artistry in all its hardship and glory.

While a contemporary work opens the show, Levan Chogoshvili’s The Donkey’s Way – gathering various elements of the avant-garde movement, it concludes with the film installation Deda Ena (mother tongue) by Meggy Rustamova. The polyphonic story of identity and individual and collective memories questions the notion of migration and the mark it leaves on successive generations; a pertinent message by the Belgian artist born in Georgia.

More information on Europalia Georgia here.

The avant-garde in Georgia (1900-1936)

Until 14 January

Bozar

Rue Ravenstein 23

Brussels

Photos: (main image) Irakli Gamrekeli, Set design for Ernst Toller’s Play Masses Man © Art Palace of Georgia - Museum of Cultural History, Tbilisi; ©David Nestorovich Kakabadze. Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid; Gigo Gabashvili, A Woman with Wings, 1910 © Sh. Amiranashvili Museum of Fine Arts; Kirille Zdanevich, Sketch for the play Maelstrom, 1924 © Art Palace of Georgia - Museum of Cultural History, Tbilisi; Niko Pirosmani banquet des quatre citadins Museum of Cultural History, Tbilisi; Petre Otskheli Sketch for The Flying Painter, Art Palace of Georgia; Petre Otskheli Sketch for the movie The Winged Painter1936