- Daily & Weekly newsletters

- Buy & download The Bulletin

- Comment on our articles

Before Time Began: Contemporary Aboriginal art centre stage in new exhibition

An exhibition honouring Aborigine art has opened for the first time at Brussels’ Art & History Museum. Running until 29 May, Before Time Began was first staged at the Opale Fondation in Lens, Switzerland, and includes some 100 works from this previous show.

The Brussels exhibition has added an introductory section presenting anthropological objects, loaned largely by Belgian institutions such as the Africa Museum in Tervuren, the MAS in Antwerp and the MIM in Brussels. It concludes with works by photographer Michael Cook that confront Australia’s colonialisation of its indigenous people.

But the main focus is on contemporary art that explores the concept of Dreaming, a mythical and complex process of creation that stretches back to 65,000 years ago. If largely rooted in oral history, it’s common to all Aborigine communities across the vast country, however isolated and disparate their language groups.

Visitors are first greeted by displays of objects, ranging from sacred burial totems, spears and boomerangs to musical instruments, including examples of the iconic didgeridoo, originating from Arnhem Land. Also deriving from this region in Australia’s Northern Territory are a series of timeless bark paintings, bold geometric designs in earth tones (pictured above). They date only from the 1950s, although the tradition is an ancient one.

These works on bark serve as a transition to the main section dedicated to contemporary artists, revealing the evolution of an art movement that dates from the early 1970s. It's one that is simultaneously bound to ancestral tradition while advancing it. Artists adopted bright acrylic paint rather than natural pigments and replaced bark by canvas and wooden boards. Although seemingly abstract with their characteristic circles, dots and wavy snake lines, they reflect the nomadic experience of living and surviving in the hostile environment of the outback.

If the desert is marked by the movements of legendary ancestors in their wanderings – Dreamings – their encounter with everything living, animals, plants and other human beings, plus natural elements such as fire, water and stars, is immortalised in works of art illustrating a profound respect of nature.

It was in 1970 that a small group of men in Arnhem Land gathered to paint on pieces of wood their interpretation of the desert, drawing on an ancient iconographic visual language. A year later, the first artistic cooperative, Papunya Tula Artists, was founded. Across the country, isolated communities with varying languages gave birth to different cooperatives, each offering their representations of Dreamtime. Ronnie Tjampitjinpa’s almost traditional concentric circle-like shapes and parallel lines (pictured above), is an example of their varying approaches.

The connection with nature reflects the concern about the changing climate. Water and its shortage has always played a key role in Aborigine culture. Severe flooding in 1972 provoked numerous artists to interpret Waterdreaming, including Johnny Warangula Tjupurrula's Water Man (pictured above), painted in gouache.

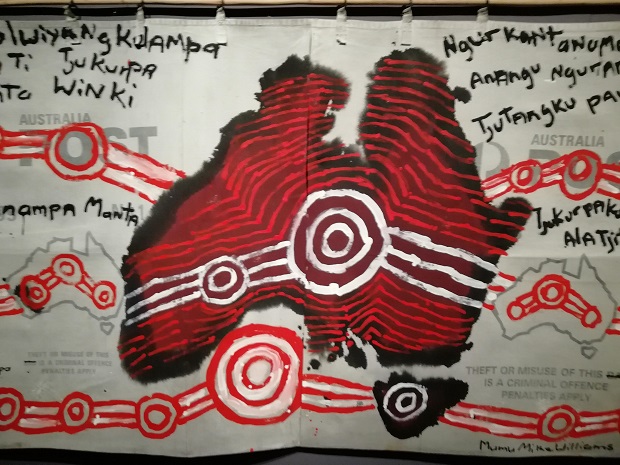

Women were originally excluded from painting on wood, or their contributions overlooked. Their output increased from the 1990s, showing a more characteristic and colourful style. More recent works by artist collective APY in central Australia include the significant work Women’s Law Alive in our Country (main image). Barbara Moore, also from the APY collective, honours her homeland in My country (pictured above), choosing a looser and bolder abstract style that nevertheless remains tied to place.

Forming part of the cornerstone of the exhibition are two intriguing large-scale installations. A women’s collective is behind Two Trees, 2018 (pictured above), drawing on their artistic heritage to pay tribute to the abundance of the natural world. Woven in natural fibres, it's an accessible but detailed scene, surrounded by animals, birds and insects that evoke the ancestral spirit.

Dominating the space is the awe-inspiring Kulata Tjuta – Kupi kupi (Many Spears; pictured above), created in-situ from 1,500 wooden spears and other objects, including photographs. Arising from an APY collective project, it invokes a mini tornado to represent the impact of the western world on traditional life.

More recent works reference present-day life in communities, such as Tiger Yaltangki’s Tigerland, 2018 (pictured above). Colourful mobile sculptures referencing pop culture are suspended in front of the monochrome wooden-panelled installation.

The final section of the exhibition is devoted to two photo series by Michael Cook where he explores notions of civilisation. In the first, Civilised, he reverses the history of colonialism by presenting portraits of Aborigines dressed in the costume of the four European powers that first visited Australia, positioning them with the sea in the background (pictured above). They feature extracts from journals by early explorers denigrating the Aborigine people. The second series, Object, reflects on the dehumanisation of slavery by creating detailed tableaux that reverses the roles of owners and slaves by placing white people in the position of objects.

Co-curator of the exhibition and curator of the Fondation Opale, Dr Georges Petitjean, believes that there are many misconceptions about Aborigine art and culture. “People think of it as one homogenous group, but there are about 200 languages being spoken and there are cultural differences.”

If the underlying concept of Dreaming is a unifying factor, variations are overlooked. “The didgeridoo is seen as typifying Aborigine culture, but it only belongs to one small part of Australia, Arnhem Land,” he points out. “We see many paintings with dots in it to the point that some people call Australian art dot painting. It’s an important element and is used to bring visual dynamism to paintings, but it’s certainly not true for all artworks,” adds Dr Petitjean.

“While drawing on ancient art, you find contemporary things like guitars. The visual language that you see of concentric circles is iconography that you will find in rock paintings that are thousands of years old. These paintings are not inspired by the old art, they are a continuation of it.”

After around 30 years studying Aborigine art, the Brussels born-and-bred art historian is delighted to bring the original artworks to his hometown. “I have studied in Australia and spent time in desert country with Aborigine people, so for me personally, it’s bringing two worlds together. It’s also important for the Aborigine people to be in Brussels. They realise that it’s important as the capital of Europe and I’m very happy to share their stories with us.”

Before Time Began

Until 29 May

Museum of Art & History (Cinquantenaire Park)